CLAS hosts semester’s second Research Colloquium

Mar 9, 2020

For the second time this semester, CLAS faculty from a variety of disciplines came together and presented on their recent research at the February Faculty Research Colloquium. The gathering featured three different presentations, with topics ranging from geology to language learning to music education.

“Collaborative teaching, or co-teaching, is a partnership of two trained teachers who work together to plan and implement lessons,” said Professor Beth Gibbs. “In music, you see this primarily in secondary school when teachers collaboratively lead ensembles, and not in elementary education. But I believe there’s an opportunity to do this with pre-service elementary teachers.”

Over the course of her sabbatical, Gibbs worked with two different elementary music teachers to work out different methods of collaborative teaching that could benefit student teachers. For one teacher, Gibbs assisted with third grade and autism spectrum classes; for the other, first grade and kindergarten.

“There’s six co-teaching approaches,” said Gibbs. “There’s one teacher, one observer, or one teaching, one assisting. We started with one teach, one assist, where I participated in musical activities, assisted with setting up and passing out instruments, and accompanied the teacher when performing songs. It helped build rapport with students, and with new teachers it can help build teaching skills. The second was one teach, one observe, which we used for assessment.”

Gibbs also implemented parallel teaching, station teaching, team teaching, and alternative teaching, which she found had a variety of potential uses for student teaching.

“Station teaching is something that I used with the third grade class – we developed a rhythm station activity with four stations that engaged them in the same content, but in a different way at each. Student teachers are familiar with different ways to approach student response, but this lets them implement principles of universal design in-person. It also allows them to interact with smaller groups of students at a time, which is helpful for transitioning to larger numbers later on. Team teaching can also help integrate student teachers into an already-set classroom experience and routine.”

Gibbs wasn’t the only faculty member presenting on teaching strategies. History Professor David Eick and Modern Languages and Literatures Professor Janel Pettes Guikema spoke together on a collaborative project that brought their two subjects into the same classroom — the implementation of an educational roleplaying system called “React to the Past,” where students reenact historical conflicts by playing as key figures from the time period.

“Reacting is used in over 500 universities in the United States and abroad,” said Eick. “In these games, big ideas clash. Students have to read rich texts and master their arguments, and are given specific goals through their victory objectives. They need to collaborate, conduct library research, take creative initiative, write persuasively and practice public speaking. Grand Valley is leading in using these games in foriegn language teaching.”

An American project led by Barnard College Professor Mark Carnes, React to the Past games are largely written and played in English. Eick and Pettes Guikema, however, are adapting and translating relevant games — such as Rousseau, Burke and Revolution in France, 1791, The Enlightenment in Crisis and Modernism versus Traditionalism: Art in Paris, 1888-1889 — for French classes.

“According to the American Council on the Teaching of Foriegn Languages, a novice language learner is capable of identifying words and carrying simple conversations, an intermediate can apply it to themselves and talk about daily life, and advanced is describing in more detail,” said Pettes Guikema. “But most of the stuff in Reacting to the Past, creating and expressing original ideas, would be identified as ‘superior.’ When we started, we predicted that even if students are only at the intermediate level, students would be able to jump up to superior proficiency to meet the goals of the game. We’ve seen that to be true.”

Meeting victory conditions not only drives students to obtain a masterful understanding of French history and culture, but over the language itself.

“Anecdotally, we had a student say that she advanced more in the language playing games here at Grand Valley than she did spending a year abroad in Léon,” said Eick.

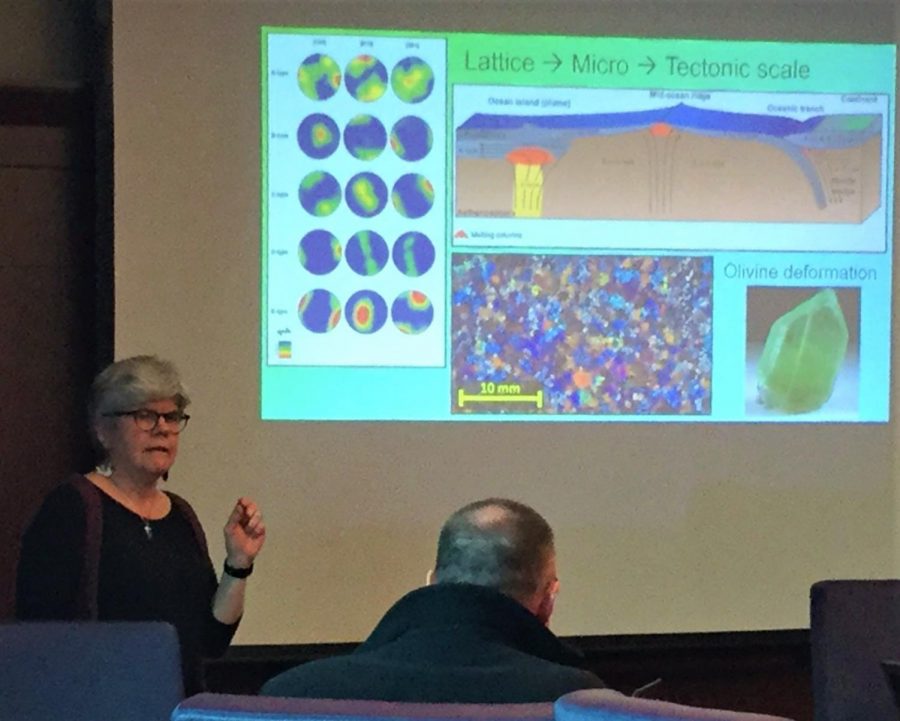

Another faculty member reporting on her collaboration with students was Geology Professor Ginny Peterson, who has not only been working with Professor Jeffery Rahl at Washington and Lee University but GVSU students Ben Pummell and Ryan VanOss.

“I work in the Appalachians, particularly with the mineral olivine — called peridot in the colloquial lingo — which forms mainly at the base of crust, the elements influencing the formation of mountains,” said Peterson. “Earth’s outer ridged layer is made up of plates moving away from each other or towards each other, and mountains forming where they’re converging. We know what’s happening on the surface, but it’s harder to know what’s happening down beneath. But when we look at old mountain belts where a lot of the rock has eroded, I can look at the guts of the mountain, which gives us an idea of what’s happening with the new mountain belts that are building today.”

Many geologists have done experimental work with high pressure, temperature and water to figure out how, when and why olivine deforms. When they publish the textures, grain sizes and shapes of their samples, field scientists like Peterson can compare their results to olivine removed in geological surveys and decipher what’s happening beneath the earth’s surface.

“When you deform olivine, the grains start to prefer a direction and cluster,” Peterson said. “They’re active under different conditions of water, temperature and stress, so we can look at them and determine what happened to them. We put it under a scanning electron microscope to look at the directions of the grain by polishing it down to thirty microns thick and putting it in a glass slide. Olivine at this size is absolutely beautiful. It crystalizes when it deforms.”

The next College of Liberal Arts and Sciences research colloquia will be held on Thursday, March 12. Like the previous, it will begin at 3 p.m. in Padnos room 308.