Species Stronghold: Reptile Conservation in Michigan

The Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake was the main feature of the seminar “Reptile conservation in the Midwest using landscape ecology and genetics.” (Courtesy/Eric McCluskey)

Nov 16, 2020

When people discuss saving species from the danger of extinction, it’s often the endearing animals that come to mind: cute pandas, powerful tigers, hilarious penguins. But the truth is that many of the species disappearing from the ecosystems they’re needed in aren’t endearing to humans at all. In fact, some of them are disappearing specifically because humans didn’t want them around.

Such is the case for the Eastern Massasauga Rattlesnake. The species is listed as “threatened” under the Endangered Species Act, a status that indicates it will likely become endangered in the foreseeable future. Like many other species native to the Midwest, the draining of wetlands for the sake of human construction and expansion has not been kind to their population numbers.

Unlike other species, however, many of the states in which they live had active bounties out for rattlesnakes before the animals came under protection. As the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service notes in their profile for the Eastern Massasauga, “people seem to have an innate fear of snakes […] Massasaugas are often killed when they show up near homes or businesses, and people may go out of their way to kill or even eliminate them.”

Despite humanity’s natural aversion to venomous snakes, many are working to preserve their spot in the Midwestern ecosystem. One such person is Eric McCluskey, a postdoctoral fellow at Grand Valley State University’s Department of Biology. McCluskey has been studying the Eastern Massasauga’s habitats and life histories in order to better inform conservation efforts, a project that has had him working alongside the USFWS and many other wildlife preservation organizations.

“As a conservation biologist, it’s been very rewarding interacting with the people who are putting conservation research into practice,” said McCluskey.

McCluskey presented his research on the Eastern Massasauga on Friday, Nov. 13 as a part of the AWRI Seminar Series, hosted virtually over Zoom by GVSU’s Robert B. Annis Water Resources Institute.

“My journey with the Massasauga started in Northeast Ohio, while I was working on my dissertation,” McCluskey said. “After two years of surveying, I had only discovered a single population. The current landscape is much more forested than it was historically — which is problematic for a species that requires open canopy grasslands to survive.”

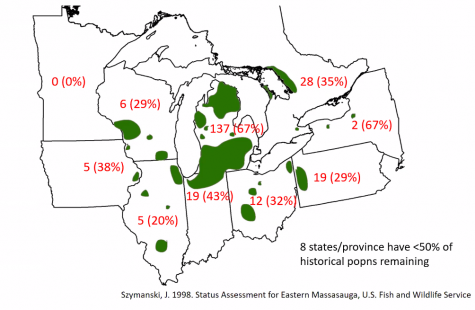

According to McCluskey, the Massasauga’s position is similarly dire in other Midwestern states like Illinois and Pennsylvania.

“Michigan is the stronghold for this species,” McCluskey said. “From 1850 to 1950, you see a lot of land conversions for agriculture in Ohio and Illinois, and nowhere near as much in Michigan. A lot of Massasauga habitats were wiped out in the process of converting these areas to agriculture.”

After his project finished in Ohio, McCluskey came to the Massasauga’s last stronghold in the Midwest: Michigan. His project focused on Bois Blanc, an island located in Lake Huron’s Straits of Mackinac. Known as “Bob-lo” by locals who eschew the French pronunciation, the island has very few residents (though it still experiences natural disturbances like logging or tourism).

“I’ve seen more snakes on Bob-lo in two hours than I’d seen in Ohio in two years,” McCluskey said. “The island has almost every kind of habitat Massasauga are found in. Being such a great landscape with abundant snakes, we thought it would be interesting to look at the landscape’s genetic structuring and diversity.”

They found that despite the scarcity of motor vehicles, the presence of even unpaved roads on Bois Blanc had a negative effect on the snakes. The closer to a road a sample was taken, the lower its rate of gene flow — the transfer of genetic material between two populations. This means that roads prevent the animals from migrating between populations, forcing them to reproduce only within their smaller gene pools.

McCluskey has seen similar difficulty with roads during his current project, which focuses on four different species of turtles: Blanding’s, Eastern Box, Spotted and Wood. The new study is underway in Manistee, Michigan, the only region in the Midwest where the habitats of all four species overlap.

“The risk with the turtles is road mortality,” McCluskey said. “Females get hit a lot more, as they have to try to leave the wetlands to go nest. You see dead turtles a lot driving site to site. Because turtles live a long time, it can look like an area has a large, healthy population — but in reality, almost all the surviving turtles are male, and in the years to come you’re looking at a serious drop in numbers. Even a really healthy, ideal habitat can be endangered just by the presence of roads.”

Blanding’s, Spotted and Wood turtles are all endangered throughout much of their range in the Midwest, while the Eastern Box turtle has been classified by Michigan as potentially vulnerable. Though the Eastern Massasauga itself is only threatened, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service considers it to be an Indicator Species — a “warning bell” that something is seriously wrong with Midwestern wetlands. By taking steps to conserve the Massasauga now, we’re protecting the natural systems that are home to many more plants and animals that will be in similar danger if the Massasauga continues to decline.