OMA celebrates César Chávez, undocumented immigrants

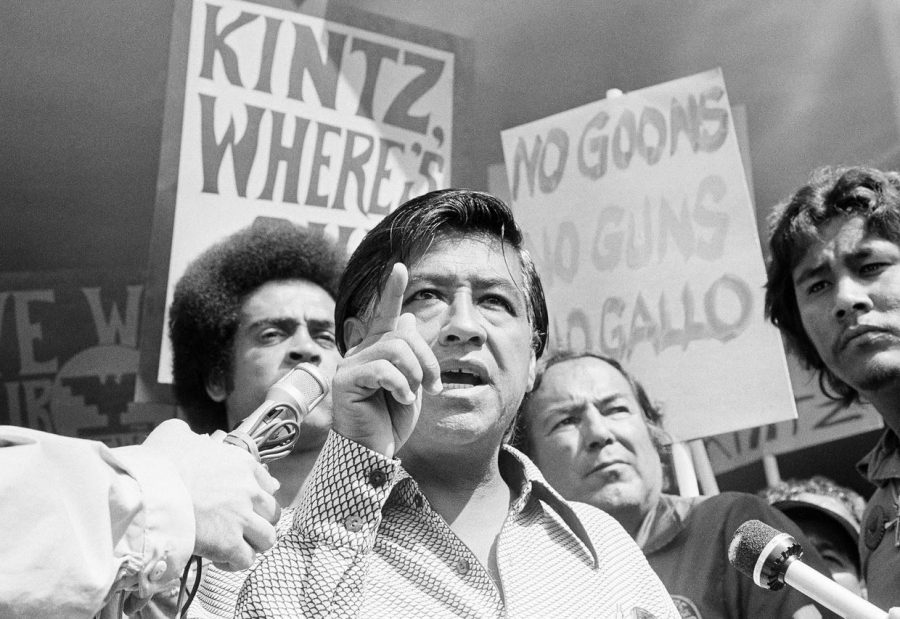

The labor leader drew influence from the nonviolent tactics of Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi, organizing picket strikes and boycotts. (Courtesy Associated Press)

Apr 5, 2021

Last week, the Office of Multicultural Affairs held their annual celebration of the life of labor leader, community organizer and civil rights activist César Estrada Chávez. Famous for his leading role in the Delano Grape Strike, a massive protest of the Coachella farming tycoons that forced the growers to cooperate with the union of immigrant laborers, Chávez was successfully able to negotiate for higher wages, the introduction of a health plan and safer working conditions in the fields.

“Prior to César organizing, there was no water in the fields for people to drink,” said David Villarino Gonzalez, the current CEO of the late Chávez’s Farmworker Institute Of Education And Leadership Development and Chávez’s son in law. “There were no toilets in the fields – how indignant. There were no protections from pesticides, workers would just be sprayed along with the crops. They were viewed as tools to implement.”

Villarino Gonzalez began working with his father-in-law as a young adult, acting as a community organizer and even as Chávez’s bodyguard when the powerful California growers put out a contract on the labor leader’s life in 1974.

“César taught me to be a negotiator, to organize workers and plan strikes,” Villarino Gonzalez said. “Senator Ted Kennedy sent his Secret Service to train us to protect César. We studied how Bobby Kennedy was murdered, how Malcolm X was murdered. In the end, César died of natural causes. I’m proud of that.”

Though Villarino Gonzalez discussed Chávez’s accomplishments, he emphasized that the real lesson of the activist’s life was that it was the common people coming together, not the work of any individual leader, that allowed for the success of the farmworker unions.

“The perfect leader does not exist,” Villarino Gonzalez said. “Perfection is not of this world. The farmworker’s movement was not just César, it was tens of thousands of people taking leadership. It’s the role of leaders to think about how other people can be great, to empower other people.”

The Chávez E. Celebration focused heavily on the rights and struggles of immigrant farmworkers, a subject the Office of Multicultural Affairs (OMA) is continuing to focus on with their first-ever UndocuWeek, a virtual series intended to uplift those living with undocumented or DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) status.

At 7 p.m. on Monday, April 5, the OMA is hosting an Immigration 101 lecture; 6 p.m. on Tuesday, April 6, a presentation on Grassroots Advocacy; and 7 p.m. on Wednesday, April 7, a panel with the Michigan Network for Undocumented Immigrant Success.

“The panel consists of three young individuals who are impacted by undocumented and/or DACA status,” said Adriana Almanez, the Associate Director of the OMA. “They serve on the leadership team for the MNUIS, which is a network for folks throughout the state of Michigan to connect with and get support from other undocumented/DACAmented individuals. One of the panelists is a GVSU alumnus.”

Another organization, the Michigan Coalition for Undocumented Student Success, will be presenting at the Grassroot Advocacy event with One Michigan for Global Majority.

“The MCUSS advocates for best practice and policy regarding undocumented/DACA support at institutions of higher education,” Almanez said. “The group was led by me for the past three years, where I served as chair. They will share what allyship and advocacy look like and how individuals can get involved.”

Though the César E. Chávez Celebration and UndocuWeek were not organized as a continuation of each other, they both intend to share lessons in immigrant advocacy with the Grand Valley State University community.

“When immigrants come here, they come here with a lot of skills and a lot of experience,” Villarino Gonzalez said. “Just because we went to college, or we’re administrators, does not mean that we’re not equal. Racism and discrimination are learned behaviors, taught by people who have power in their worlds. In English, power sounds kind of dirty. In Spanish, poder, translates into the ability, the capacity to do something. It means empowering somebody. That was the motto of the United Farmworkers: Sí, se puede. Yes, we can.”