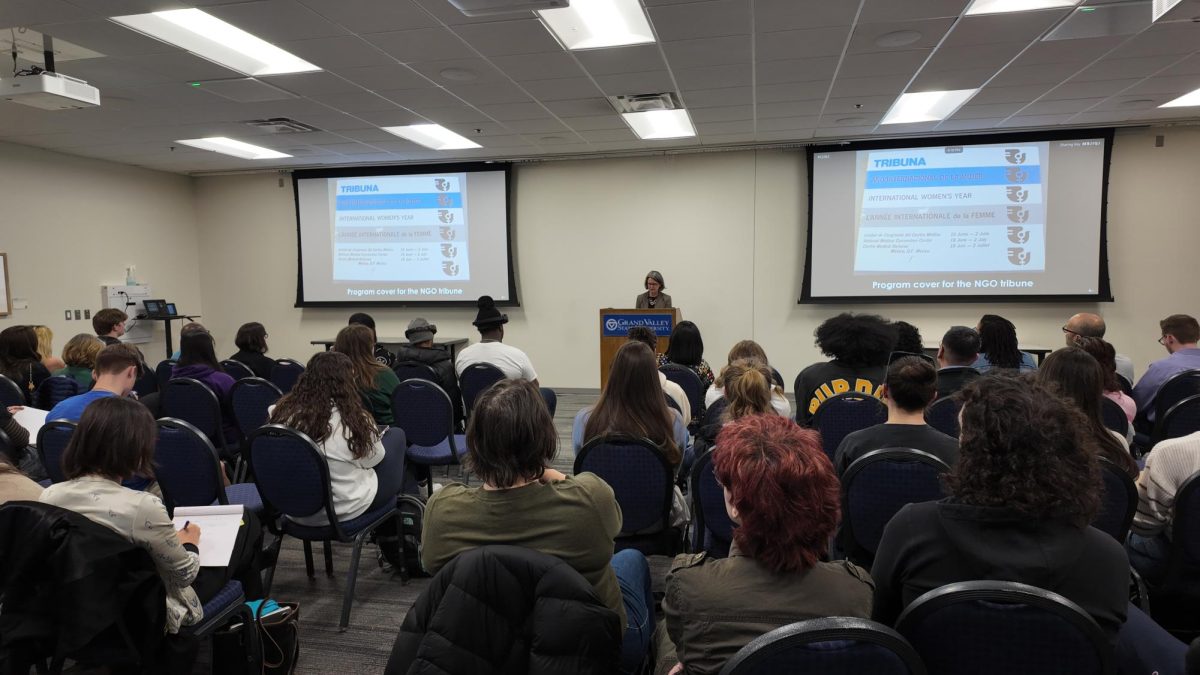

Pulitzer Prize-winning author and University of Michigan historian Heather Ann Thompson, Ph.D., spoke at the 48th Annual Great Lakes History Conference (GLHC) at Grand Valley State University on Oct. 5. Thompson gave a presentation on the significance of the Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and highlighted the importance of equality and human rights within American prison systems.

GLHC is a history-centered event hosted by GVSU at the downtown Grand Rapids campus from Oct. 5 to 7. The theme of this year’s conference was “Division and Reaction.” The event featured three keynote speakers and numerous historical panels held by GVSU faculty as well as guest contributors and attendees from universities across the nation.

Thompson, a Professor of History and African American Studies at UM, gave a presentation entitled “The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Why it Matters Today” based on her book “Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and Its Legacy.” She was awarded both the Pulitzer Prize and the Bancroft Prize among multiple other awards. The New York Times called the book, “a masterly account of the Attica prison uprising, its aftermath and the decades-long legal battles for justice and accountability.”

Through her presentation at GVSU’s Loosemore Auditorium, Thompson addressed the “broken U.S. criminal justice system” while walking the audience through the violent events of one of the most deadly prison uprisings in United States history: the Attica Prison Riots.

The Attica Prison Riots took place at the poorly maintained Attica Prison in upstate New York, in 1971. Inhumane living conditions and unjust treatment eventually led to an uprising that caused 39 inmate and hostage fatalities at the hands of law enforcement.

Living conditions of Attica Prison frequently left prisoners sick and dying from sepsis, surviving on $0.63 of food a day, one roll of toilet paper a month and frequent mistreatment by the prison guards. Thompson said the state of the situation and the events of the riot are often overlooked.

On Sept. 9, 1971, a door failed to lock and the prisoners took power of the facility. Thompson recounted the tension as the prisoners’ guards were taken as hostages and demanded of better representation, parole, religious freedoms, less censorship of mail and, eventually, amnesty for the prisoners.

Thompson said the prisoners had no intention of killing these hostages. Some prisoners were actually friends with the guards, finding common ground in the poor conditions in which the prison operated. When a helicopter flew over the prison on the fifth morning of the riot, the prisoners held out hope that New York Gov. and former Vice President Nelson Rockefeller would make an appearance to partake in negotiations, however, a second helicopter appeared and instead deployed tear gas.

“If you know anything about tear gas, it isn’t a gas. It’s a powder. And it sticks to the mucus membranes of your eyes and goes down your throat,” Thompson said.

The police stationed outside were untrained for riot control and stormed in with guns blazing. 39 people were killed; 10 correctional officers and 29 prisoners. The remaining prisoners were taken back into the prison, where they were refused medical care, forced to crawl over broken glass and suffered other cruel punishments.

Once perceived as a riot perpetuated by the prisoners, Thompson said the state of New York covered up the true events with the help of the federal government.

The story that was fed to the public was the prisoners killed the correctional officers, but autopsies later showed the correctional officers died from gunshots and not the knives the State of New York claimed the prisoners used to kill them. Thompson said these voices were too little, too late. It took decades for the prisoners to finally receive a $12 million settlement and have their names cleared.

Thompson urged the audience to understand the importance of the prison riots and how they apply to our world today.

“Attica matters. At some moment in American history, we change what we believe is possible in our justice system,” Thompson said.

The events of Attica prison weren’t fully recognized, and are still frequently glazed over in history. Thompson said the way history is framed changes the way the events are perceived, which is why the Attica Prison Uprising is such an important piece of history.

“Historians see that the preponderance of violence in the 1960s was state violence. And somehow we came out of the 60s saying ‘we need to give the police more, not less power,’” Thompson said. “How does that happen? Well, it’s based on how we tell stories and if we tell the story wrong.”

Because true events were concealed, victims of incidents like the Attica Prison Uprising went unheard and individuals were able to gain power from falsehoods. Thompson said this is why events like these matter, calling it a “very powerful story of how that happens.”

The other keynote addresses of the 2023 GLHC conference included Kevin Boyle, Ph. D., William Smith Mason Professor of American History at Northwestern University and Randal Maurice Jelks, Ph.D., Professor of African and African American Studies and American Studies at the University of Kansas, who also addressed political violence and injustice in American history.

Panel facilitators included the faculty of GVSU, the University of Olivet, Hope College, Aquinas College, the University of Michigan-Dearborn and Albion College.

With many elections up and coming in November, Thompson encouraged the audience to actively participate and do their part in political activism for criminal justice systems in the United States.

“Understand how the prison pipeline works in your community,” Thompson said. “Vote.”