Although students are often the subject of discussions surrounding workload management, professors face a similar struggle.

On Feb. 28, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) hosted a discourse event inviting GVSU professors to discuss faculty workload. Faculty expressed frustration and concern around how their true workload and efforts are being represented in reports, and in turn, compensation.

The AAUP is an organization that advocates for and defends the values of university professors and their roles in higher education. The AAUP Advocacy Chapter began in 2020 at GVSU, following faculty’s concerns for working conditions and expectations. Since then, the organization has posted several memos regarding policies on relevant issues to campus faculty, most recently publishing a statement of support for the United Auto Workers (UAW) Labor Action.

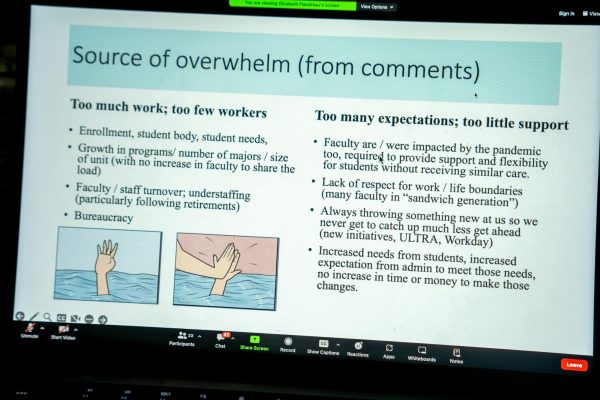

The organization’s recent GVSU chapter meeting focused on the manageability of faculty workload. Faculty attendees gave their perspectives on “invisible” work not considered by official job expectations, like the extensive time writing emails, scheduling appointments or finding ways to recruit students to their departments. Faculty shared available solutions to workload problems, and whether the workload is manageable for them.

At GVSU, faculty workload is mapped and decided in a Faculty Workload Plan (FWP). The plan is filled out by faculty who identify their scholarship, teaching, and service activities like advising student groups or curriculum development.

Following the collection of information in the FWP, faculty then submit their Faculty Workload Report (FWR) to the Office of the Provost. The FWR categorizes and tracks faculty workload by outlining courses taught, service activities undertaken and outcomes of their Significant Focus for the year. The report compares anticipated work with the Faculty Workload Plan with actual accomplishments and any additional tasks performed.

However, many faculty members feel the Faculty Workload Plan and Report does not provide a clear picture of the tasks and duties they fulfill.

“That document is not helpful,” said Associate Professor Sherry Johnson of GVSU’s English Department. “It’s not reflective of all of the work that we do.”

The FWP and the FWR are integral factors in determining faculty salary. However, the “invisible work” not under official job expectations or outlined in those documents goes unappreciated.

At the meeting, Johnson said the FWR is just another document that unnecessarily increases professors’ workload.

Associate Professor Mayra González of the Department of Modern Languages and Literatures said the university has favored programs that will teach students more immediately applicable skills. This encourages faculty to take on further tasks to draw administrative attention to their programs to receive more recognition for the work they do.

“That translates into all the faculty constantly looking for ways to be seen, recruit and bring the message, with very little structural support,” González said.

Such factors also contribute to unappreciated workloads.

González feels the lack of structural support was seen after language placement tests were transitioned to an online format. González felt this transition was a decision of which faculty were notified too late and was made without regard for its impact on the Spanish program. Consequently, this change resulted in poor student placements and mishandling of AP credit transfers– fallout that led to an increased workload not outlined in the FWP or appreciated in the FWR.

“It feels that we’re constantly going against the grain,” González said.

The AAUP’s chapter event highlights how the organization advocates issues like workload, aiming to provide a platform for faculty to voice their opinions and advocate for their needs within the university. The AAUP is the premier university professor advocacy group that has popularized some of the most important faculty governance standards and policies, in particular the 1940 Statement on Academic Freedom and Tenure and the 1966 Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities.

The GVSU AAUP Advocacy Chapter has even addressed issues surrounding students, including the cost of education and student debt. The chapter is different from the formalized governance, which constitutes much of the issue-based discussions surrounding faculty working conditions. An advocacy chapter does not have the same formal structure as typical faculty governance.

“Its goal tends to be to talk as directly as possible with faculty members to figure out what their burning concerns are right now,” said Associate Professor of Philosophy Andrew Spear and Secretary GVSU’s AAUP chapter.

After the concerns are heard, the advocacy chapter will appeal to formal governance to address said issues. Formal governance at GVSU is organized as committees that address various, but specific issues. Spear said these committees include university administrators, whom faculty may imagine as their “boss.” In this sense, formalized governance might contribute to a “chilling” effect on advocacy and discussion.

“It can be a liability because faculty may struggle to speak freely,” Spear said.

Spear said fair compensation and recognition of the university’s faculty is necessary to provide students with the best educational foundation possible.

“Faculty working conditions are student learning conditions,” Spear said.