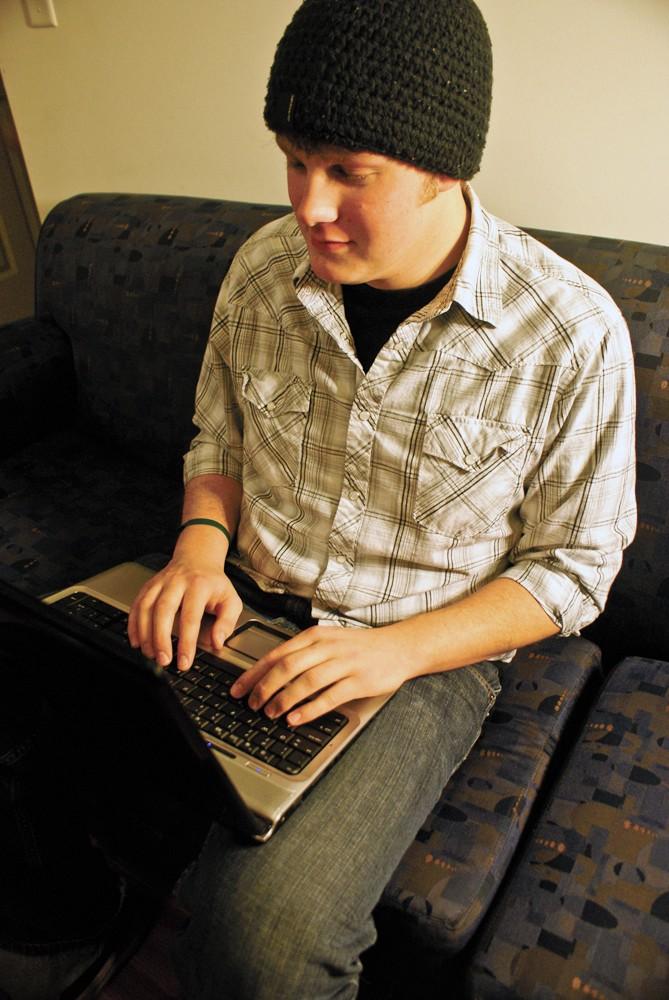

Illegal music downloading carries consequences

GVL Archive / Eric Coulter Illegal downloading is enforced at Grand Valley State University

Oct 10, 2010

Whether it’s blasting from the speakers at a house party or playing on an iPod, music is an integral part of college life. But with students usually working within the confines of a tight budget, some turn to illegal downloading in order to get the latest songs.

Last week, Grand Valley State University released its annual copyright law statement to all students in order to inform them of the university’s policy on illegal downloading.

“People don’t realize it’s illegal,” wrote John Klein, associate director of Academic Systems, in a statement. “If it’s something you would have otherwise had to pay for, why would you think you could get it for free?”

Capt. Brandon DeHaan, assistant director of the Department of Public Safety, agreed some students do not “use common sense” while on the Internet and may not even realize if they break the law.

“There are some people who are very naive about that sort of thing,” he said. “But if something seems too good to be true, it usually is.”

Although software such as Limewire is legal itself, using it to download copyrighted material is still illegal.

“The software is legal,” said John Wezeman, Computing and Technology Support Help Desk supervisor. “It’s what you’re using it for to get the songs (that is illegal). They’re legitimate programs. They have legitimate uses. It’s just that they’re being used for the wrong uses.”

In addition to legal concerns, Klein added that downloaded files can potentially contain viruses and harmful malware.

Although the university does not screen for illegal downloading, it is still bound by law to respond to any complaints from copyright holders such as the Recording Industry Association of America or the Motion Picture Association of America.

“We do not go out specifically looking for this,” Wezeman said. “It is reported to us by whoever owns the copyright and then we are required by law to follow up … We are not going through and specifically scanning and looking for these files.”

If the university receives a complaint from a copyright holder, the suspected student’s Internet is deactivated and the student must sign a written agreement promising not to continue downloading files illegally before his or her Internet access will be restored.

Klein said “99.99 percent of the time” downloading investigative cases end at the first step phase. But if a student is detected making illegal downloads a second time, he or she is required to talk with the Dean of Students before the Internet is reactivated. Since 2001, GVSU has handled “hundreds” of outside copyright claims within the GVSU judicial system, Klein said.

To date, no GVSU student has been sued for downloading copyrighted material over the university’s Internet network, and no criminal charges have been filed.

However, Klein stressed that this does not make illegal downloading at GVSU “safe.” Students caught downloading music, videos, software or other copyrighted material can still be subject to civil lawsuits from the copyright holders. Under the U.S. Copyright Law, fines are assessed on a case-by-case basis. Copying more than $1,000 worth of material can result in fines of up to $250,000 and 10 years in prison.

According to the Institute for Policy Innovation, music piracy costs the recording industry costs the recording industry $12.5 billion each year.

“With investigators deployed in cities across the country, the RIAA is working closely with law enforcement to pull pirate products off the street and to demonstrate that the consequences for this illegal activity are real,” the RIAA website reads. “We are continuing our efforts to educate fans about the value of music and the right ways to acquire it and, when necessary, to enforce our rights through the legal system.”