Senate passes act to combat infringement

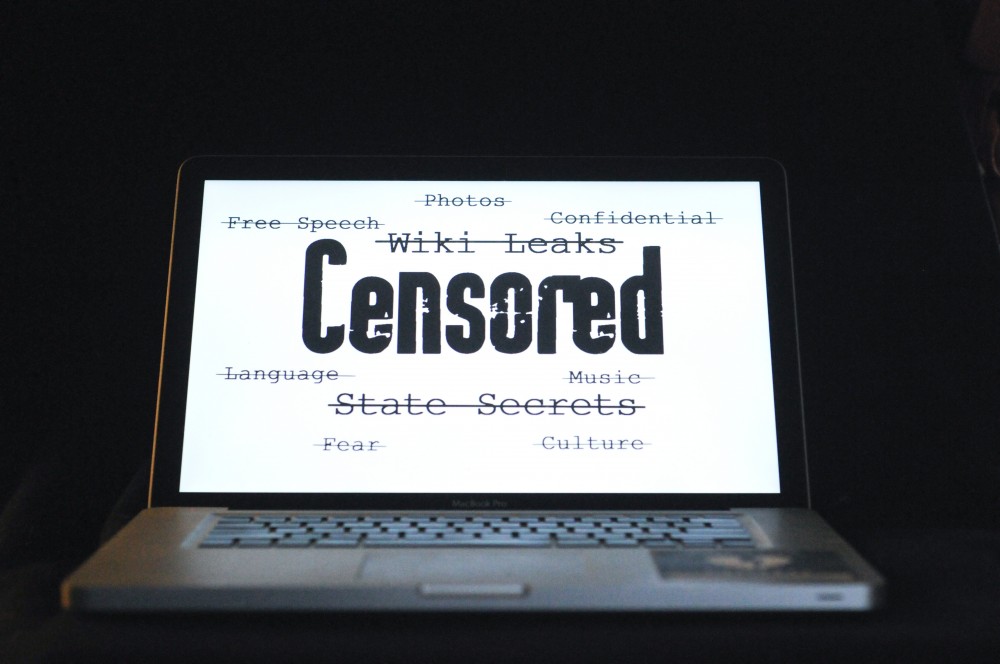

GVL Photo Illustration /Andrew Mills An illustration depicting proposed rules of online censorship that are currently being debated. If passes, the government will be able to limit access to sites that may cause security problems.

Jan 17, 2011

A bill giving U.S. agencies and officials the power to pursue websites that sell counterfeit goods and pirated music, movies and books was passed through the Senate Judiciary Committee in a 19-0 vote.

The “Combating Online Infringement and Counterfeits Act” (COICA) was passed through the Senate with little time left in 2010 to reach the Congress and be signed into law. However, with the backing of major companies, including Disney, Nike, Merck and Time Warner, the pressure to sign the bill into law is on.

COICA allows the Justice Department to seek a court order against the domain name of websites alleged to be assisting activities that violate copyright laws, based on the judgment of the U.S. attorney general.

The bill was met with criticism from politicians like Senator Ron Wyden (D-Ore.), who said “deploying this statute to combat online copyright infringement seems almost like using a bunker-busting cluster bomb, when what you need is a precision-guided missile.”

Although the critics of the COICA are calling the bill “internet censorship,” supporters of the bill, such as co-sponsor Senator Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), said that bills such as this are important to the future of the American economy, job creation and protecting intellectual property.

Roger Moiles, affiliate professor in the political science department at Grand Valley State University and expert on public policy, said he would liken the bill to the Napster issue in 2000 when record companies persuaded a judge to issue an order to stop the site from facilitating file sharing. A lawsuit proceeded for lost royalties.

“Think of how quickly something can go viral – once some site makes a file available, there’s not much chance for the artist to get control of it back,” Moiles said. “And in the end, Napster agreed to pay millions of dollars to settle it.”

Although the bill enables the attorney general to take legal action to shut certain sites down, action in itself would only be a temporary measure since the site could fight it in court, Moiles said.

“The idea of this is not unprecedented,” Moiles said. “For example, if it’s determined that a model of automobile has a safety defect that endangers the consumer, the federal government can order a recall of the vehicles, rather than waiting for people to be injured or killed and then file their own lawsuits for damages.”

Moiles said as the bill is written, he does not see it as much of a censorship issue because the government would not be telling the sites what they could and could not say, but rather focus on the questions of the owners’ posted files.

Moiles said that the COICA bill has the potential to affect college campuses like GVSU in regards to file-sharing sites like Napster. However, the bill’s threat does not far exceed the threat file-sharing sites already pose.

“Every so often, the record companies get aggressive, especially with downloading on college campuses, and they’ll make an example out of some student by getting a huge judgment over copyrights,” he said. “So the sites this bill would affect may already be an issue for students. If they’re downloading protected files, then they may be liable for damages regardless, with or without this bill.”

Although the bill aims at shutting down offending websites, Moiles said that the measures are likely only temporary.

“Suppose you shut down a particular domain they use. Unless you seize all their files and equipment – which goes beyond what the bill proposes – they’re just going to start up again under a different domain name,” he said.

Moiles added that the bill “might simply be impractical, maybe unenforceable.” He said that although the bill has potential to extend its reach to restrict other information such as WikiLeaks, federal courts would have the last word on whether or not it was an infringement on free speech in the end.

“But the more likely basis for this bill is simply money,” Moiles said. “The entertainment and media corporations want protection for their products, and they contribute a lot of money to congressional campaigns.”