American music is Black music

Feb 15, 2021

For the first time in quite a while, the Super Bowl’s halftime show was led by a single artist — that artist being Abel Tesfaye, better known as The Weeknd. Tesfaye is of Ethiopian descent, and much of his music style is taken from other Black artists.

Claiming two of his main musical inspirations to be Michael Jackson and Prince, Tesfaye’s pop-infused R&B style is not uniquely his own. He has drawn upon many different artists, particularly those who are Black, throughout America’s history to create his own voice.

In retrospect, America has done the exact same thing. It is impossible to fully understand and describe the history of American music without examining the Black music that created it.

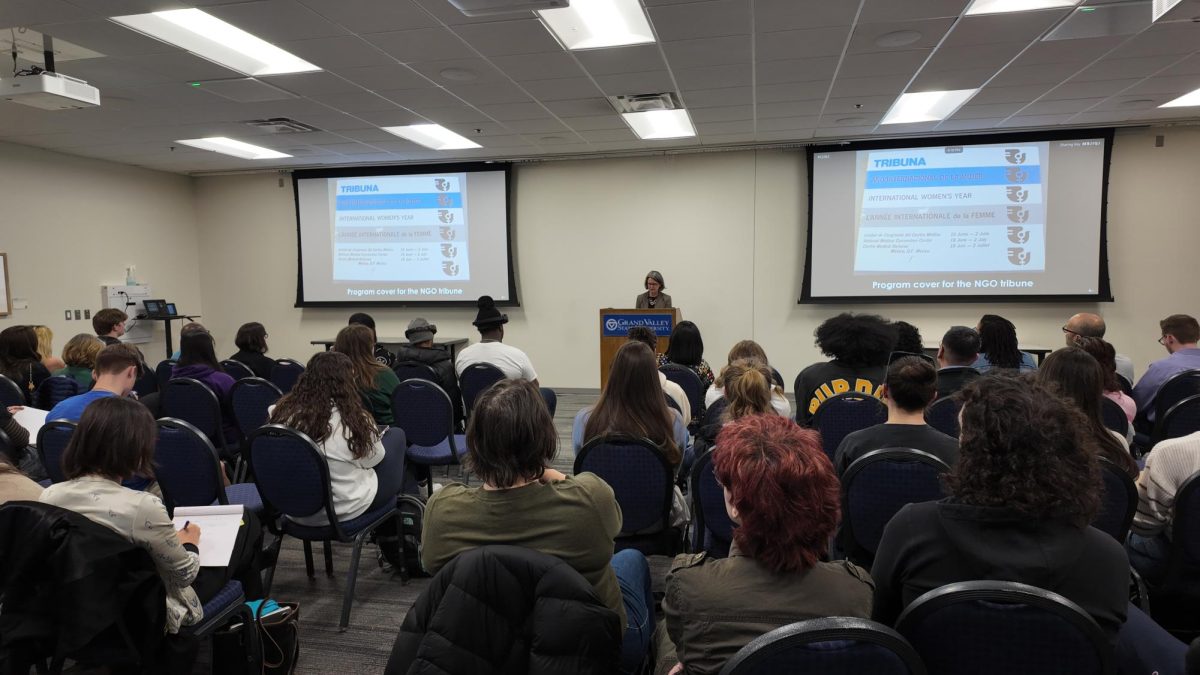

Eric Harvey, assistant professor in the school of communication at Grand Valley State University and editorial adviser of the Grand Valley Lanthorn, has been a music critic since 2007 with a doctoral degree in Communication and Culture and Ethnomusicology. He also recently wrote a book about hip hop which is set to be released in October.

Harvey said to explain music in America without first realizing the influence that Black people have had on its creation is entirely unrealistic.

“The easiest way to say it is there is no popular music in the United States of America without African Americans,” Harvey said. “Point blank, 100%, I’ll take it to the grave. I will fight anybody who disputes this. Popular music really reflects the degree to which African American cultural traditions have contributed so much toward what we love.”

Jack Hamilton, Associate Professor of Media and American Studies at the University of Virginia and author of, “Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination,” said he agrees with Harvey in that American popular music and Black music are, and always will be, bonded together.

“It’s literally impossible to imagine the music industry of today without the influence of Black artists and Black culture,” Hamilton said. “The history of American popular music and the history of Black American music are essentially inseparable — there isn’t a single genre of contemporary popular music that isn’t fundamentally rooted in Black musical traditions.”

The Black American experience is one full of hope, struggle and determination, much of which can be felt and heard through their music and the genre being examined.

When slaves were first brought to America, they did their best to bring their beloved music and cultural traditions with them. As the slaves were converted to Christianity, European classical music and Black musical tradition fused to create a new form of spiritual music.

This spiritual music did not just serve as a way of sorrowful worship, but as a code used to coordinate escapes or rebellions. Spiritual songs soon died down, but not without resurgences throughout the Civil Rights Movements.

Many historians consider Black spiritual music to be folk music, and it is known to be an unsullied legacy of African oral tradition.

Next up came the 1920s, where the influence of work songs, spiritual music and Black tradition created blues music. In order to cope with the violent, cruel realities of the Jim Crow laws in the South, the blues tunes offered an escape for the Black community who sang them.

Being able to be played by readily available, or even homemade, instruments, blues was a form of music that was accessible to anyone regardless of their economic status or race.

Another genre born out of the fusion of different styles, jazz is a melting pot of the musical traditions of French-speaking Creoles, African Americans and white Europeans in New Orleans.

Segregation laws in 1894 divided the dark-skinned Creoles from their lighter-skinned brothers and sisters, hence giving Black Creole musicians more of a desire to associate themselves with Black people who spoke English, mixing their musical styles.

Soon enough, Black workers on riverboats spread jazz to Missouri and Kansas, and later the nightclubs in Southern Chicago.

Although it may come surprisingly to some, many of the origins of rock ‘n’ roll come from the Black community in America as well.

The most direct evolution into rock ‘n’ roll came through the rhythm and blues type songs played during the 1940s and 1950s which the record companies called “race music.”

The first rock music was created with a Black audience in mind, the songs being linked with the migration of Black Americans to other parts of the country as part of the war effort during the industrial boom taking place at the time.

The music was well received by white teenagers for its new, edgy sound, soon leading it to be rebranded as a white genre.

Born out of Black communities in the 1970s, hip-hop has come to represent Black American culture. Referring to more than just rap music, hip-hop’s birthplace of the Black urban community has led it to represent deejaying, breakdancing and graffitti.

Hip-hop’s creation was heavily drawn from Caribbean immigrants who brought mobile DJ units and forms of rap to the neighborhoods. It was also inspired by soul, R&B and funk hits in past decades.

No matter what decade it was performed in, hip-hop has continuously proven to be an important vessel for Black empowerment and social commentary.

All of this has led to popular music today to have an intense, undeniable Black influence. Yet, this influence still fails to be recognized on a daily basis.

Hamilton said he feels that recognizing the contributions Black Americans have made to the music industry is the historically correct and responsible thing to do. He said that failing to do so means you simply do not understand American musical history.

“The history of American music has largely been defined by white people really loving Black music while mistreating and dehumanizing the people who make that music in all sorts of ways,” Hamilton said. “So, I think that recognizing those contributions more fully is a form of redress for a very long history of injustice. I don’t think it’s a remotely sufficient form of redress just on its own, but it’s still important.”

Langston Wilkins, the Director of the Center for Washington Cultural Traditions, a program of Humanities Washington and the Washington State Arts Commission, said the appreciation of American music today should stem from the appreciation of the Black people who helped to create it.

“You cannot understand American music without acknowledging and understanding the influence of Black Americans,” Wilkins said. “Yet, Black musical contributions remain under appreciated. That’s such a shame. Music is innovative, but it also typically builds from prior forms. Lack of appreciation for Black musical contributions will be a detriment to future music production and reception.”