GV celebrates Constitution Day

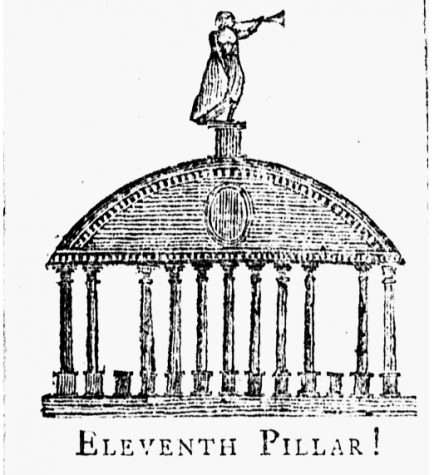

“The Federal Pillars” drawing, first published in the Massachusetts Centinel, January 16, 1788. (Courtesy / Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division)

Sep 20, 2021

Following their late-night decision on Sept. 1 not to block a now-infamous Texas abortion law, the Supreme Court has featured heavily in headlines as Americans debate not only the law itself but its “bounty” based method of enforcement. Many of these arguments revolve around “Roe v. Wade,” which affirmed a Constitutional right to safe and legal abortions, having yet to be overturned: arguably making the law itself unconstitutional. To complicate matters further, Senate Bill 8 specifies that defendants being accused of enabling abortions cannot argue that the law is unconstitutional as a defense.

Only a few weeks later on Sept. 17, the United States celebrated Constitution Day, in memory of the document’s original ratification in 1787.

“In contrast to the previous Articles of the Confederation, the new Constitution pointedly omitted any assertion that each state remained sovereign,” said Akhil Reed Amar, Professor of Law and Political Science at Yale University, at the Constitution Day Celebration hosted by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies. “The new Franklin/Washington plan expressly proclaimed that states must always and everywhere bow to the supreme law of the land formed by the federal Constitution.”

The proposed Constitution would only bind states that agreed to it, and even then only if nine or more of the original thirteen states agreed. Ultimately, the Constitution won the popular vote in eleven of thirteen states (North Carolina and Rhode Island remained sovereign, independent, and separate from the United States until 1789 and 1790, respectively).

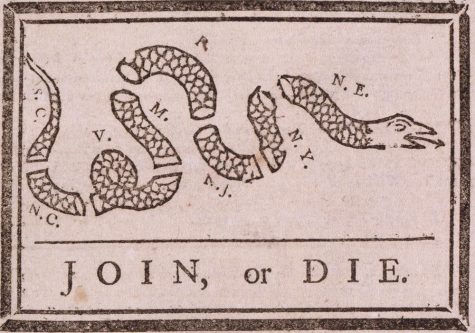

Amar has a history with the Supreme Court, having served as a clerk for then-Judge, now-Justice Stephen Bryer as a younger man. Years later, in his career as a legal scholar, he’s been cited as a source by Supreme Court Justices across the political spectrum in over forty cases. In his presentation of a chapter from his new book “The Words That Made Us: America’s Constitutional Conversation, 1760-1840,” Amar showed the audience the political cartoons that had contributed towards popular attitudes surrounding the developing Constitution, including Ben Franklin’s original invention of the medium with his 1754 “Join or Die” snake segmented into thirteen colonial pieces. Later, after 1787, cartoons featuring the imagery of the “Eleven Pillars” holding up the federal government became popular as well.

“No pillar, once up, could be unilaterally removed lest the great federal dome, supported by and in turn supporting the pillars, tumble to the ground,” Amar said.

The two missing pillars, depicted in cartoons as toppled or cut off at their base, would be persuaded to ratify the Constitution themselves after its first ten amendments, The Bill of Rights, which addressed many of the most frequent objections to the Constitution that arose during the original ratification process. Unfortunately, laws quickly emerged that were in violation of this new section of the Constitution.

“The Bill of Rights,” Amar said. “I wrote a whole book on it, and it means nothing for the first hundred years, truth be told. And I like the thing, I have a soft spot in my heart for it. But it says congress, for example, can’t pass a law abridging the freedom of speech and of the press. Congress passes such a law, and President John Adams enforces it ruthlessly. It’s a law that makes it illegal to criticize John Adams, and so much for the first amendment, until further in our story.”

Though a negative interference, it wouldn’t be the last time a President influenced the Constitution. Amar argued that the most important change to the Constitution in the history of the United States was Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which laid the groundwork for the fourteenth and nineteenth amendments.

“Presidents turn out to be pretty important actors in our constitutional system,” Amar said. “Even if you think courts are important, who picks judges? That would be Presidents. Presidents are supposed to pick judges, judges aren’t supposed to pick presidents. I just, by the way, explained the problem with Bush vs. Gore in passing.”

But despite the importance of the Presidency to the Constitution (as Amar points out, it was designed with George Washington in mind as a strong executive), more important to the Constitution than any individual is America as a system: which is exactly why it’s important for voters to be informed about the underlying laws of our country.

“Every four years, we pick a President,” Amar said. “You are the hiring committee. And you need to understand what a President needs to do, and what the rules are, because the first thing a President does is raise his or her hand and pledge to preserve, protect and defend the Constitution of the United States. And if you don’t understand the Constitution, you won’t be able to tell if they are doing a good job.”

Those interested in watching a recorded version of Grand Valley State University’s Constitution Day Celebration can find it online on the Hauenstein Center’s Youtube page. The chapter Amar presented at the event, “The Memes That Made Us,” can be read on the Lapham’s Quarterly website.