GV STEM students present research across the country

Nov 15, 2021

One of the benefits of undergraduate research is the opportunity for students to present their scholarship at academic conferences and showcases, where they can get practice at sharing their work as well as form potential connections with others in their field. For nearly two years now, however, the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated that many of these gatherings be conducted virtually— which, though safer, lacks many of the benefits of an in-person event.

“The virtual conferences are a totally different experience,” said Grace Miller, a McNair Scholar studying cellular and molecular biology. “Really all you can do is upload a poster, maybe add a voiceover of you reading it. You can’t watch people look over your poster to see where they stop, what their reaction is. Last year, I didn’t get any questions on my poster at all. If I could, I would never do a conference virtually again— although, unfortunately, I am doing one this Friday.”

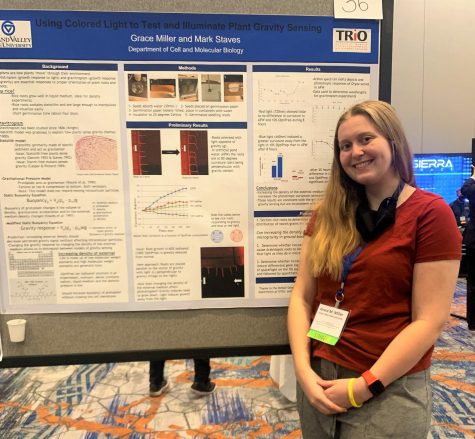

Luckily for Miller, as vaccination rates have risen over 2021, so have the number of academic conferences returning to an in-person format. This fall semester has been the first time that many student scholars have had the ability to travel across the country and present their research since March 2020. This month, Miller herself had the opportunity to fly to Baltimore, Maryland for the annual American Society for Gravitational and Space Research Conference, which lasted from Nov. 3-6.

“This was my first in-person conference,” Miller said. “It’s basically a bunch of space nerds all getting together to talk to each other. I was so happy to be able to go from poster to poster and understand what people were presenting on— some referenced papers I had actually used myself in my own manuscripts. Of the presentations that were the closest to my field, a lot of them I was familiar with the lab that they’d worked in, which was so cool.”

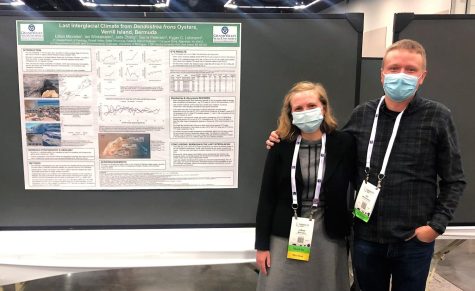

Lillian Minnebo, a Student Summer Scholar and recipient of the Koeze Fellowship, had a similar experience when attending the Geology Society of America Connects 2021, which was held from Oct. 10-13 in Portland, Ore.

“From a student standpoint, four years through my education in geology, I loved being able to go to some of these talks and think, I know exactly what they’re talking about,” Minnebo said. “To the majority of the people there, my own poster presentation was on a newer topic, so I had to do a lot of explaining. But there were so many nice people there, they were curious and wanted to know. And then there were a few who already understood, which was very exciting.”

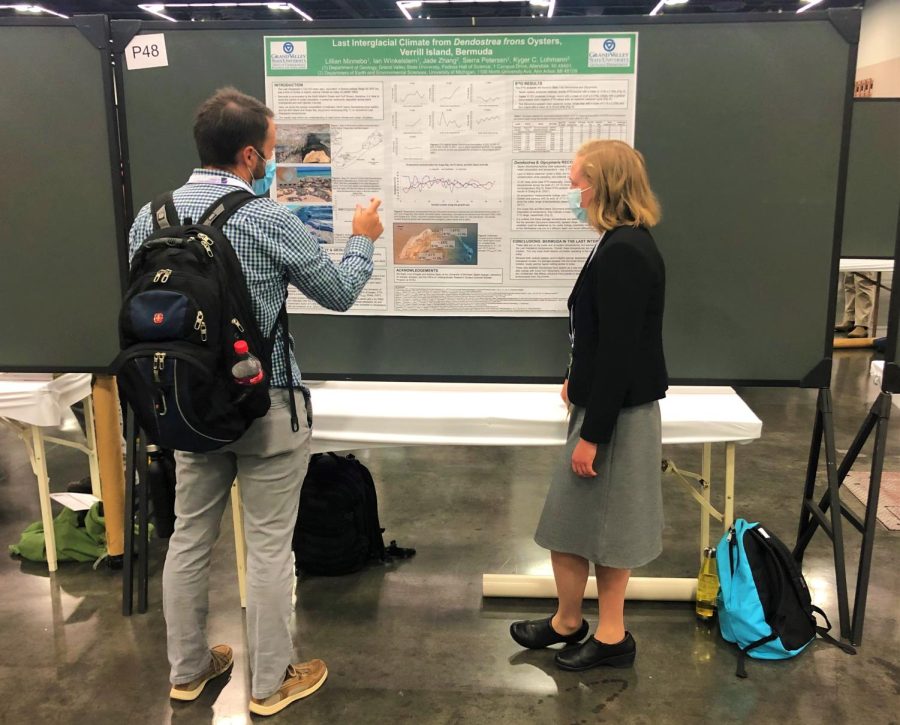

Minnebo’s research is on paleoclimate: she takes samples from the shells of fossilized oysters, which are then analyzed for the ratio of heavier and lighter isotopes. The remnants of each can be used to reconstruct the temperatures that the long-dead oysters experienced when they were alive.

“The shells have growth layers, which are similar to tree rings,” Minnebo said. “I use a small Dremel drill to sample the layers, which have a seasonality curve. Our oysters are from the last interglacial period, which had a climate very similar to today, if not slightly warmer.”

The 116,000 to 129,000-year-old oysters Minnebo has sampled so far were collected in Bermuda, and analyzed by a lab at the University of Michigan.

“As the climate gets warmer, the ice caps in the poles melt, which contributes cooler water to the oceans,” Minnebo said. “That changes the ocean circulation, which then has an effect on the continents. Bermuda is a great place to study a changing climate, because it’s isolated by the warmer gulf stream. That’s what paleoclimate is— using chemistry, biology, and geology to answer questions about climate change, which is a subject I’m very passionate about.”

In contrast to Minnebo’s use of long-dead fossils to study the climate of the earth, Miller uses living plants to study hypothetical growing conditions in space.

“I study the mechanism of plant gravity sensing,” Miller said. “There are two models on how plants might be sensing gravity. One is the long-popular statolith theory, which states that starch grains inside the cell membrane will fall to the lower part of the cell, and that tells the plant ‘there’s gravity!’ We’re trying to see if that currently accepted model is accurate or not— and right now, my research is pointing ‘not.’”

The second, newer theory is the gravitational pressures model, which posits that outside of the membrane, there’s tension at the top of the cell and compression at the bottom.

“We grow rice plants in a dark room with a unilateral light, in a box with artificial pond water,” Miller said. “We change the density of the water the rice grows in, which gets in this in-between layer and increases the buoyancy of the protoplast— everything in a cell beneath the cell wall— without entering the membrane. If the gravitational pressures model has any validity, this basically should confuse the cell’s ability to sense gravity. So in our experiment, we increased the buoyancy, and surprise: it does affect how they sense gravity. If the statolith model were accurate, we wouldn’t have observed any differences.”

The density of the water is changed using an iodixanol solution called OptiPrep.

“It’s nontoxic, which is very important, because a lot of naturally occurring dense liquids are pretty toxic to plants,” Miller said. “You don’t want to, for example, put mercury in there. We’re going to do the same thing with an Arabidopsis plant, and then do some genomic analysis to see if we are causing the genes that are expressed in microgravity on the international space station to be expressed here on earth. Are we stimulating microgravity? Because then this would be a much cheaper way to do so than sending a plant up to the ISS, which is a million dollar project.”

Given that the results of Miller’s research challenged the popular statolith theory, she understandably received a lot of questions about her data, which gave her an idea on how to improve her presentation for next time.

“Going forward, since I had a few ‘critics,’ I would add another QR code to my poster with supplementary data,” Miller said. “One big question that came up was growth, are they growing less in this medium? And I knew the answer was no, and I had collected the data to back that up, but I hadn’t had room for it on my poster. Without having it in front of them, they would say ‘well, I don’t know, maybe you’re mistaken.’ Next time, I’ll be prepared to show them more.”

Despite the ‘staleolithers,’ as she calls them, Miller had a great time presenting at the conference.

“A realization that I had flying out to this conference— and I was the only Grand Valley student attending, it was just me and my faculty mentor Dr. Mark Staves— was that this was something that I could do,” Miller said. “It wasn’t going to be this big, intimidating thing anymore. Even though undergrad biology is mostly women, you sometimes feel the pressure that you might not be cut out for this… and I will say, this conference was almost entirely white men. So it was cool to go there and say, ‘look at my poster, look at this research,’ and have confidence. When I got back to my hotel room after presenting, I was just happy dancing, because I thought, ‘oh my gosh, I just did that! In front of NASA people who are basically famous.’”

Minnebo was joined at the Geology Society of America conference by several other GVSU student presenters: Madeline Mennega, Nathan Shelnick, Riley Murphy, Hanna Szydlowski and Michael Stefanou.

“I knew them all, since the GV Geo department is pretty small,” Minnebo said. “I flew in with Hanna— it was actually my first time on an airplane, which was exciting. My presentation was a culmination of all everything I’ve been studying, and I’m super grateful for my mentor Ian and the OURS program for supporting me in research. It’s been one of the greatest experiences I’ve had at Grand Valley.”