Eternals marries the visions of Marvel’s founding fathers, sets exciting precedent for Marvel Studios

Feb 7, 2022

Marvel’s “Eternals” started streaming on Disney+ on Jan. 12. It premiered in November of 2o21, but due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic (and the obscurity of the titular characters), audiences didn’t exactly flood local cinemas to catch last year’s cosmic installment in the Marvel Studios saga.

Some superhero movie fans and purveyors of high culture are only catching “Eternals” now — and with all the superficial takes out of the way, perhaps there’s some space for an involved, thoughtful evaluation.

For anyone who hasn’t seen the movie yet, but would still like to, there’s one important spoiler-free observation to make (which will absolutely be elaborated on, with spoilers, later).

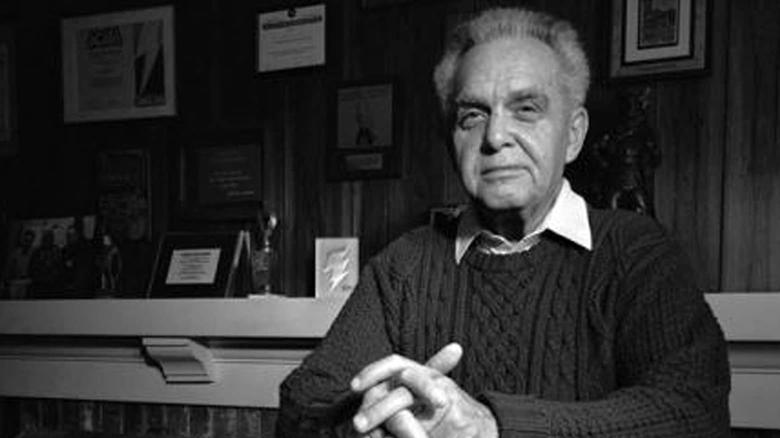

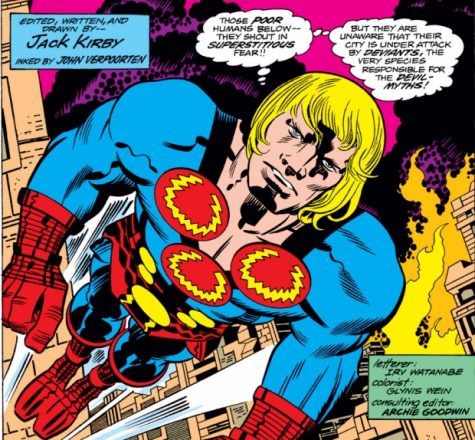

The original comic books of the seventies that “Eternals” is based on were written and drawn by Jacob Kurtzberg, better known by his pen name, Jack Kirby. Kurtzberg drew and helped write the first appearances of the X-Men, the Avengers, the Fantastic Four, Captain America and Marvel’s iteration of the folkloric Thor. Kirby’s collaborator on his more successful projects, Stanley Lieber (better known as Stan Lee), had nothing to do with the Eternals comics.

Kurtzberg was a genuine master of the comics form, fully deserving of his nickname “King Kirby.” Many of his stories were convention-breaking, progressive and compelling tales about larger-than-life, modern-day myths and legends.

In spite of this, his Eternals comics ring hollow. Flat, two-dimensional characters, echoes of his similarly-cosmic-yet-higher-quality New Gods stories for DC Comics and unfortunate “Ancient Aliens” style colonialist stereotypes pervade the 19 issues that made up his original run.

“Eternals,” the movie, brings Lieber’s storytelling sensibilities to Kurtzberg’s dry, stoic cast of characters. In Chloe Zhao’s movie, the heroes laugh, love and hate their way through a cosmic, Lovecraftian plot. Before redefining superheroes as complicated, relatable figures, Lieber wrote romance comics and horror stories, centered around the insecure, miraculous human experience.

For audiences that love the fusion of drama, humor and action present in Marvel Studios and Marvel Comics staples like the Avengers and X-Men (whose characters have been well-acquainted with that approach since the sixties), “Eternals” gets to explore this fusion for the first time.

Like a baby taking their first steps, there are plenty of stumbles, which could easily induce secondhand embarrassment, but seen through a very specific lens, viewers might feel a sense of pride.

(If you’re not looking to be spoiled, this is your cue to stop reading.)

In the comics, Ikaris — the flying, eye-lasering super-man of the “Eternals,” played by Richard Madden– is a heroic, noble figure. In Zhao’s movie, he’s a 6,000-year-old lonely, rage-filled man-child. That recasting is emblematic of how the story’s marriage of Lieber and Kurtzberg’s approaches skews dark and mean-spirited.

There are uplifting moments, like the crackling joy of seeing demigods punch the hell out of each other or the loving tenderness between space-god Phastos, played by Brian Tyree Henry, and his human partner, Phil. But the movie ends with our heroes killing a god mid-birth, Ikaris flying into the sun (apparently killing himself) and a merciless celestial host (aptly named “The Celestials” by Kirby) coming to Earth to judge a deeply flawed, broken humanity.

The cosmic deities of Zhao’s “Eternals” are more human than most of Marvel Studios’ most profitable intellectual properties. The perpetually righteous, essentially sexless Captain America might as well be a synthetic being compared to the flawed, loving Ikaris and Phastos. Which is ironic, given that the movie’s protagonists are revealed to actually be synthetic automatons, built by Celestials to safeguard the planet through its pregnancy with Celestial offspring — a mission our heroes deliberately undermine, in order to save the planet. The new Celestial, you see, would have destroyed the planet upon being born.

The dark, occasionally joyless and confusing nature of “Eternals” seems to lack self-awareness (which is also rare for a Marvel Studios production, to not be self-conscious). It’s an earnestly frustrating movie, which does, technically, make it bad. But it is innovative.

If Zhao could bring Kurtzberg and Lieber’s visions together, maybe the next director of an Avengers movie could strip Lieber’s ever-present drama out and elevate the heroes to legends; maybe they could totally remove Kurtzberg’s grandeur, and completely reduce Captain America, Iron Man and Thor to truly useless, pathetic characters who always succumb to infighting and never get anything done.

But, as “Eternals” has proven, those innovations could have joylessly dismal or joyfully disastrous results.