The dangerous myth of chain migration

Feb 1, 2018

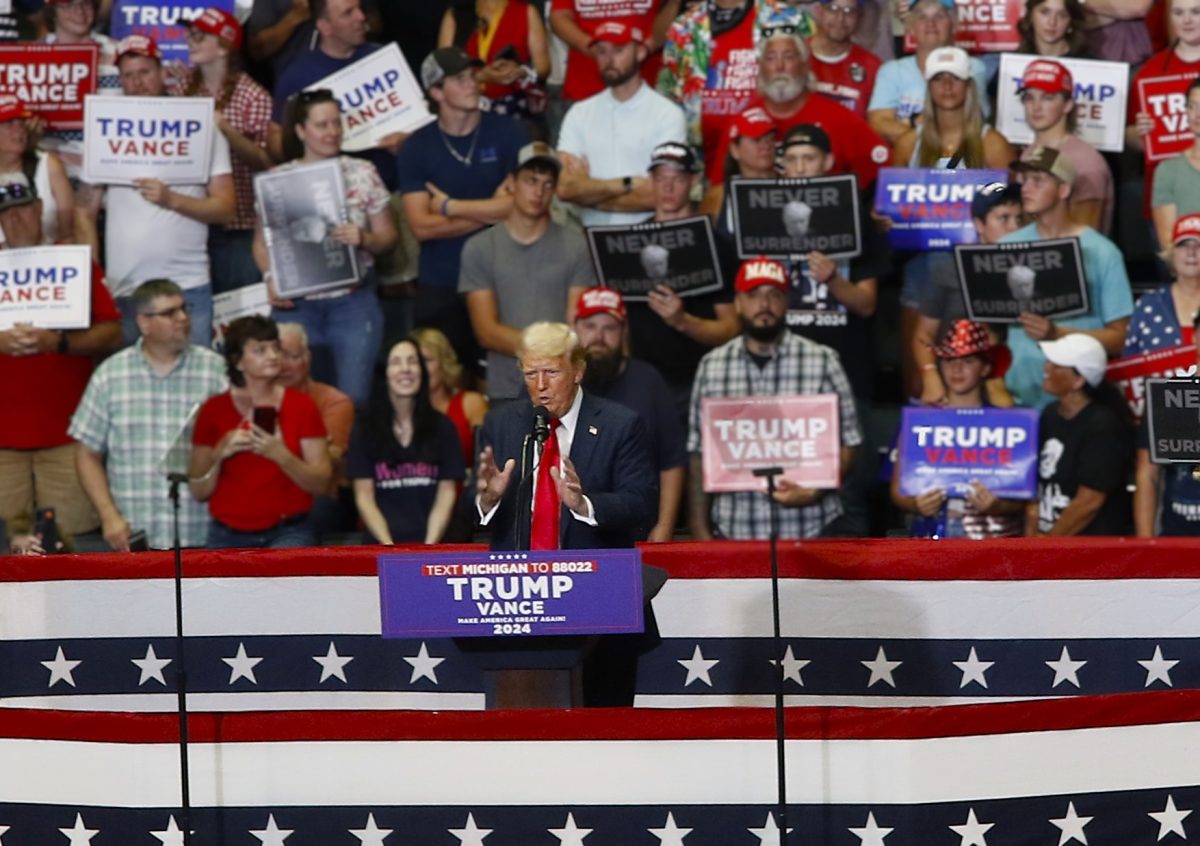

Anyone who doesn’t live under a rock could tell you that immigration policy has been a touchy subject in the U.S. for some time now. 2018 certainly hasn’t brought any improvements in this arena, and this January has been especially eventful.

First the three-day government shutdown over Democratic desire to revive the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, then Trump’s responsive plan to exchange the citizenship of many DACA “Dreamers” for his $25 billion border wall. Neither party, though for very different reasons, is interested in paying such a high price to release DACA from what is beginning to sound more and more like a hostage situation, so like many of Trump’s statements regarding the border wall, this bargain is unlikely to come to pass. But the border wall is far from the most concerning aspect of the White House’s immigration outline—at least in comparison to its plan for ending “chain migration,” a prospect especially troubling for the fact that its accomplishment seems entirely plausible.

“Chain migration” is the fun conservative buzzword used to describe our country’s family migration systems and family reunification visas the same way “Obamacare” was used to describe the Affordable Care Act. In theory, the “chain” means that once a person becomes a U.S. citizen, they can quickly bring their immediate family, spouses and children to the U.S. as well. Upon naturalization, these immigrants can petition for less-immediate family, like parents and siblings, to come to the U.S. themselves, who in turn can petition for their families to become citizens, and so on and so on until hard-working Americans have drowned in the flood of foreign invaders and our economy is ruined forever.

In practice, the General Accounting Office has long since determined that immigration waiting lists provide the limits necessary to prevent “chain migration” from ever becoming an actual threat. Each link in the chain—that is to say, each waiting list for a family visa—can take up to 25 years, thanks to widespread system backlog. In addition, any immigrant who wants to sponsor the migration of a family member to join them has to prove to the government that they would be able to provide financial support for their relative if they needed it, meaning their income has to be 125 percent of the poverty line for the number of people in their household. Not only does this exclude any immigrants relying on government assistance from participating in the family migration program, but it requires petitioning immigrants to have taken the time to settle down with a stable, well-paying job, adding even more time to the long window between one link in the chain to the next. As a result, it takes far too long for a chain to form at all for family migration to be the kind of overwhelming problem it’s painted to be by Trump’s immigration plan.

In fact, the only thing that ending family reunification programs accomplishes is catering to the fears of Trump’s far-right nativist supporters. The image of immigrants as Trojan horses for hundreds more like them—draining the government of funds to support their families and refusing to assimilate into white American culture the way European immigrants have in the past—has been used too long as a fear-mongering tactic by anti-immigration groups, and it’s foolish to cut away even more at our already-restrictive immigration policies because of it.

Xenophobia has no grounds on which to create national policy, but it unfortunately appears to be what we’re moving toward. Trump’s wall may be ridiculous, but his intention to end family migration, rooted and supported by years of nativist fear, is a concerning possibility.