Who’s profiting from America’s opioid crisis?

Sep 16, 2018

Who’s profiting from America’s opioid crisis?

Ysabela Golden

At this point it’s become pretty clear to everyone in the United States that our opioid crisis is less the accidental consequence of pharmaceutical advancement and more the inevitable result of how profitable willful ignorance can be for drug companies.

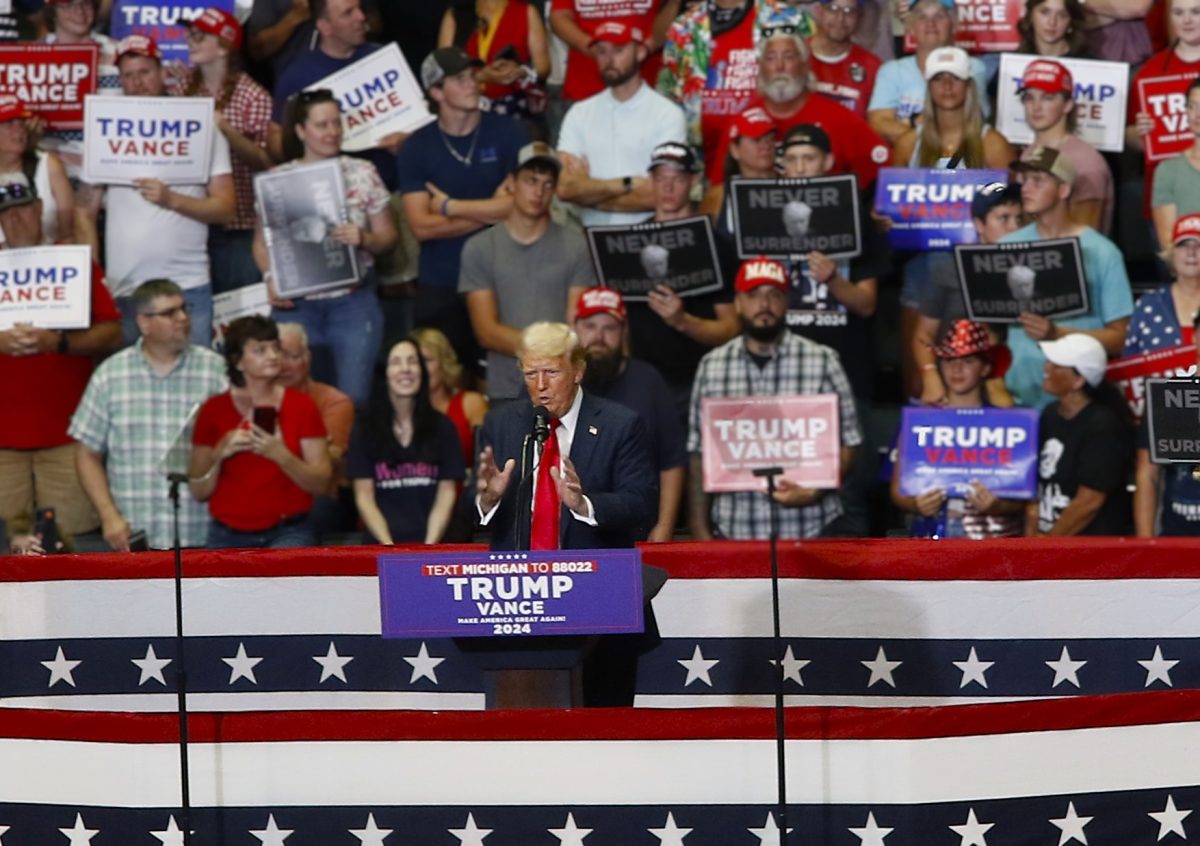

Even Trump, whose general policy seems to be hiring the private sector to regulate themselves, threatened to sue companies that manufacture opioids over the “substantial costs and significant interest” the federal government has in the epidemic. If he ends up going through with the lawsuit (though no update has come on that front since mid-August), he won’t be the first: states, municipalities and even labor unions have all jumped on the litigation bandwagon in an attempt to hit Big Pharma where they might actually notice—their wallets.

There’s a long history to these lawsuits, going all the way back to the 90’s when healthcare providers began prescribing their patients opioid pain relievers at much higher rates after pharmaceutical companies assured the medical community and fearful patients that their products wouldn’t become addictive. The result was widespread over-prescription and misuse of these painkillers before it became clear that yes, they were very addictive, and no, doctors should not keep prescribing them at the rate drug manufacturers were encouraging them to.

Still, even as recently as 2015, a Harvard study found that hundreds of U.S. doctors had been paid six-figure sums by opioid manufacturers for “speaking, consulting, and other services” – with physicians who prescribed particularly large amounts of the drugs being the most likely to get paid.

One company, Purdue Pharma (owned by Raymond Sackler and family) has gotten a significant amount of media attention for their “advertising” since earlier this year when Senator Claire McCaskill released a report naming them as the leading offender in an arrangement between opioid manufacturers and pain advocacy groups in which millions were exchanged in order to “create the necessary conditions for the U.S. opioids epidemic.”

Overwhelmed by impending litigation (and by three of their executives pleading guilty in federal court to making false claims about their product being “less addictive, less subject to abuse and less likely to cause withdrawal symptoms than other pain medications”), Purdue promised to end its aggressive promotion of their opioid pain reliever OxyContin to doctors. After 22 years of little to no repercussions in the industry, such a consequence is a welcome change of pace. Even more unusually, it’s not just Purdue employees who are facing the blowback for their dangerous business practices – its the owners themselves.

None of the Sacklers have been personally taken to court for the misdeeds of their company, but that doesn’t mean prosecutors, or the public, aren’t interested. Even more attention has been on the family since board member and former Purdue President Richard Sackler patented a new drug earlier this year —a mild opioid intended to ease withdrawal symptoms – making many who have been hurt by the opioid crisis outraged at the idea that the family that profited so much from the problem they helped create would also try to profit off of a solution. Previous to the media buzz surrounding their role in the opioid crisis, the family had been best known for their philanthropy. The Sacklers have funded museums, art galleries, colleges —they even have an institute of science at Yale University. But as OxyContin has undergone more and more scrutinization, the public has started to realize the cost behind the Sackler family’s philanthropic ventures.

Considering the epidemic of addiction and overdoses that paid for their overseas galleries, it does seem right for the Sacklers (and the rest of their pharmaceutical peers) to be part of the solution. But not for a paycheck—if these billionaire philanthropists really want to help end the opioid crisis, they should be the ones footing the bill.