A legacy, not a name: Exploring the life of Sister Ardeth Platte

Feb 24, 2020

Sister Ardeth Platte’s voice is kind and gentle. The first time we spoke, we chatted for over an hour about the incredible life she’s lived, and she ended the call by saying she wanted to learn more about my life.

“Bless you in what you’re doing,” she told me before she hung up the phone. “Lots of love.”

Much like the way Sr. Platte spoke to me, the work that has occupied the better part of her 84 years on Earth has been grounded in peace and love. But most of all, it’s rooted in justice.

________________________________

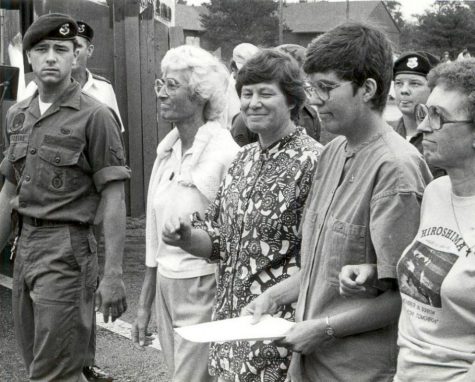

Courtesy / Nancy Phelan Wiechec

These days, Sr. Platte lives in Washington D.C. When I spoke with her, she was in California to be with her brother, who had just gotten out of surgery. She was accompanied by fellow nun and her partner-in-crime, Sr. Carol Gilbert. The two were headed back to Washington D.C. the next day but wouldn’t be there long.

They spend most of their time traveling the country, trying to rally support around the Treaty for the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). The treaty was written in 2017 by the United Nations, and Sr. Platte was there for it all. It was during that year that she and Sr. Gilbert joined the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, or ICAN.

In her 66 years with the Dominican Sisters, an apostolic community with a hub in Grand Rapids, Sr. Platte has found herself on the frontlines of several movements. She’s spent a lifetime advocating for the poor, environmental issues and the world’s total disarmament of nuclear weapons.

She may be known best for her anti-nuclear activism. While living in Michigan in the 1980s and 90s, she helped rid the state of all its nuclear weapons. Years later, she and the ICAN team received a Nobel Peace Prize for their work with the U.N.

This work has gotten her arrested on several occasions, most notably in 2003 when she was sent to federal prison for three-and-a-half years, earning the title of “terrorist” in the state of Maryland and a character on the 2013 Netflix Original, “Orange is the New Black.”

When I bring up these most talked about protests in the early 2000’s, she immediately cuts me off.

“No,” she repeated over and over again. “It was way before then.”

To Sr. Platte and others who take part in these Plowshares actions, “every loving act of nonviolence is as important as every other.” Sr. Platte didn’t care if I knew about the moments in her life that were the most publicized, she wanted me to understand why she did them in the first place. And it wasn’t because she wanted to be on Netflix.

Sr. Platte began studying Plowshares back in Michigan, and connected deeply with the movement and the community that started it all, Jonah House. In 1995 when she and her team had successfully shut down the last Air Force base in Michigan that housed nuclear weapons, she decided to pack up and move to Baltimore.

“So, there’s no nuclear weapons remaining in Michigan,” Sr. Platte said, “We thought, ‘Well, let’s go closer to the Pentagon!’”

During her tenure at Jonah House, she completed four Plowshares actions, each of which built off the last. Each action represented how nuclear weapons threatened the various aspects of our universe: water, air, space and land, respectively. Sr. Platte and her crew used their own blood to represent “the messiness of war that we want to stop,” and hammers “to get rid of that that… does not benefit society and to reconstruct and to develop something good and positive.”

Although getting arrested isn’t the main purpose of a Plowshares action, it’s definitely part of the plan.

“When we went into court and jail,” Sr. Platte said of their protest at Andrews Airforce Base, “that one was really good because we had the chance to get every bit of what is legal and what is illegal into the documents of the courts.”

This is the life of Sr. Ardeth Platte. Day in and day out, she spends her time planning her next move. The moves she’s making now, however, is what she considers her most important yet.

___________________________________

In 1970, 191 countries joined the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), a document the U.N. thought was going to stop the spread of nuclear weapons and promote peaceful uses of nuclear energy. Sr. Platte said that didn’t happen.

“Just like taxation, there are loopholes,” Sr. Platte said, “They use loopholes in the NPT to circumvent the abolishment of nuclear weapons.”

She criticized nations across the globe, especially the United States, for continuing to make and sell nuclear weapons all these years later. “What they’re doing is illegal,” she said in an exasperated tone.

“When the United States goes to war in any country,” Sr. Platte said, “We are always doing actions to unmask what they are doing that is legal or illegal. Because if you don’t hold your government accountable, they will… lie, they will steal, they will perpetuate funding that perpetuates their billionaire, millionaire clubs.”

What they will never do, she said, is what is best for the people they represent. That’s where ICAN stepped in.

When Sr. Platte and Sr. Carol heard that ICAN was planning on creating TPNW with the UN, they immediately joined in.

They, along with other international organizations, spent three weeks that summer negotiating the terms of the treaty, which were much more rigorous than NPT.

“This treaty… will end nuclear weapons,” Sr. Platte said. “I think when we end nuclear weapons… we start doing what is basically, humanly necessary for all of the country and for the world again.”

The negotiation process was almost as exhaustive as the treaty itself.

“It was like a day and night affair,” Sr. Platte said, “(It’s) where we hammered out this magnificent treaty.”

A lot of the work she’s been doing recently has been with people much younger than her, but she likes it that way. “I find younger people so much more astute as it relates to violence,” she said, crediting any progress that has been made on this front to groups led by young people like Black Lives Matter and March for Our Lives.

“I love what I see in the movements,” Sr. Platte said, comparing today’s political activism to the kind she took part in during the 60s and 70s. “I love what I see when I listen to the young… I am celebrating young people, and I know and trust that young people will… make a better world.”

In her mid-80s, Sr. Platte knows her time left on Earth is rather limited, but she’s hopeful that young people will finish the job she started. “Young people are just yearning to learn about this treaty,” she said, adding that she hopes her years of work will inspire a new generation of organizers.

If anyone knows about how impressionable one’s youth can be, it’s Sr. Platte . She grew up in the small, close-knit village of Westphalia, Michigan, an hour east of GVSU. She was raised Catholic and went to Catholic school entire life, and while social justice issues were never explicitly talked about, her activism was no doubt impacted by her upbringing.

She lived through World War II, seeing the devastating impact it had on her community and the rest of the world. She fell in love with nature through the farming she took part in from a very young age. But the real inspiration for her life’s work came after she left Westphalia.

She continued her studies at Aquinas College, which was where she first met the Dominican Sisters.

“(The Dominican Sisters) deeply inspired me,” Sr. Platte said. “They were just ordinary people, but such great people and such compassionate… people, who really taught me a lot about living.

She would go on to serve as a schoolteacher for many years, working with poor and disenfranchised students in inner-city Saginaw at the St. Joseph Alternative Education Center.

It was during this time, while working with adults, dropouts and students that were expelled from school for participating in the Civil Rights Movement, that she decided to commit her life to fighting injustice.

“It was a time of upheaval when I really learned about the injustices — especially for black people and brown people and for the poor,” Sr. Platte said. “And from that point, I just never turned back. This will be the rest of my life.”

She has never broken that promise. Sr. Platte has given her life to causes she believes are necessary for the survival of the planet. She lives modestly, disdains luxury, and doesn’t miss a beat.

“Whatever you’re going to [write],” Sr. Platte told me the last time we spoke, “I hope it’s about the issue, not the person.”

Everything you need to know about Sr. Ardeth Platte can be found in the jail cells she was kept in after trespassing onto Air Force bases and praying for an end to nuclear war next to the weapons themselves. It can be found in the garden she kept during her time at Jonah House, the fruits of which fed people in the poorest parts of Baltimore. It can be found on the streets of New York, Washington D.C., and Lansing where she’s protested with the likes of Jane Fonda and Cesar Chavez.

Sr. Platte doesn’t seem to care much if you know her name, she cares that you understand the legacy of her work.