Kent ISD schools face growing substitute teacher shortage

Mar 9, 2020

Julia LaPlaca recalls her eight-month stint as a Kent ISD substitute teacher in 2016 with mixed feelings.

“I had some very sweet interactions with children,” LaPlaca remembered. “I also had a kid vomit on my computer. Another kid pooped in a garbage can. I thought, ‘Why would you choose to do this to me now?’”

Bodily malfunctions turned out to be the least of LaPlaca’s worries.

Every day began with a scramble to accept a teaching gig, a dash through the hallway of a new school and a glance at the day’s lesson plan. Once the bell rang, 35 third-graders would barrel down the hallway, screaming as they piled into their seats.

How substitute teachers manage to keep their cool in this chaotic environment surprises LaPlaca, who says the stress of subbing outweighs the benefits.

These days, substitute teachers like LaPlaca are growing scarce, resulting in a growing shortage in Michigan from 2015 to 2019. High-need Kent ISD schools disproportionately struggle to locate substitute teachers, harming student achievement as administrators hire uncertified substitute teachers, mix up classrooms and place greater demands on teachers.

*

Veteran substitute teachers are not surprised that fewer people want to substitute teach.

When Tanya Cabala started substitute teaching across Michigan in the 1980s, she found it difficult to manage student behavior. The role grew more demanding as students began facing cyberbullying, screen addiction, attention disorders and anxiety — mental health issues that no one had prepared her to address.

“Everyone wonders why we don’t have subs, but it’s pretty obvious: the profession is in trouble,” Cabala said. “Sometimes you’ll get a crazy class just floating on the ceiling. Most days you’re just flying by the seat of your pants.”

Education professionals have discussed how substitute teaching has gained a reputation as a hard, thankless job for years. Yet researchers have only recently documented the shortage.

A study conducted by Michigan State University’s Institute for Public Policy and Social Research reports that two-thirds of school districts in Michigan (64 percent) cannot find enough substitute teachers “several times a week.” Since the 2015-16 school year, the fill rate has dropped from 93 percent to 86 percent, meaning that school districts seeking 100 substitutes for a given day might only fill 86 openings.

Nathan Burroughs, Ph.D., lead investigator, said researchers need more data before drawing regional conclusions. However, they suspect that wealthy school districts are generally more likely to fill substitute teacher openings than high-need school districts.

Local data backs up Burroughs’ hunch. EDUStaff reports that Kent ISD school districts lag behind the statewide average, with the fill rate in Grand Rapids, Wyoming and Kentwood schools averaging between 70 to 80 percent.

Cabala does not blame young people when they tell her that they feel overwhelmed by the responsibility of substitute teaching.

“Schools reflect what’s going on in society, and subs are filling in the gap so much more than they used to,” Cabala said. “I once met two young women trying out subbing, who told me if ‘we were education grads, this experience would turn us off totally.’”

*

Not all substitute teachers share horror stories like LaPlaca.

What Scott Urbanowski enjoys sharing most about his substitute teaching experience is his favorite memories of students. Watching students demonstrate the latest dance sensation or explaining what TikTok is can be hilarious.

The moments of connection with students do not erase the tense atmosphere in schools. Education professionals feel intense pressure to meet rising state standards, and administrators and teachers often distrust one another.

The search for substitute teachers adds yet another problem for administrators to worry about. Some school districts require substitute teachers to have a teacher certificate, while others drop their qualification levels to get more candidates in the door.

Michigan lawmakers recently lowered the amount of college credits required to become a substitute teacher to just 60 credits, the equivalent of an associate’s degree, to expand the substitute pool. Over 80 percent of the Kent ISD substitute teacher pool does not have an education background, according to EDUStaff, Michigan’s largest substitute teacher provider.

State Senator Winnie Brinks (D-Grand Rapids) recognizes the pressure that administrators are under to fill open substitute positions, but she says that school districts should be wary of expanding at all costs.

“We don’t want to lessen requirements just so we can have a warm body in the room,” Brinks said.

The trend of reducing teaching qualifications also concerns Elizabeth Moje, dean of the School of Education at the University of Michigan. Moje views teacher certification as a the best way to demonstrate a candidate’s understanding of content instruction and student development.

“The reduction of credit-hour requirements is extremely worrisome,” Moje said. “We’re supposed to be preparing people for college and a career. When the people who are teaching don’t have college degrees, it’s hard to imagine them preparing students for college.”

Mary Bouwenese, president of the Grand Rapids Education Association, says that when no substitute teachers are available to fill a teacher absence, administrators combine classrooms, driving up class sizes and pushing students from different grade levels together in a new, distracting environment. Kent ISD schools shuffle classrooms multiple times each week.

“I might be a fifth grade teacher with thirty kids, and now I have five first graders I don’t know what to do with,” Bouwenese said.

Moje says that when students are placed in new classrooms, they must adapt to an entirely new community. This process disrupts students’ ability to focus on course content.

“Each classroom has its own place in the curriculum, different styles of relating to one another, and its own culture,” Moje said. “Children aren’t robots; you have to help them learn.”

In addition to shuffling classrooms, administrators make teachers cover for their absent colleagues. When this happens, teachers give up their limited time for class preparation, vacation, and professional development.

Urbanowski says that school districts already grapple with record-low teacher retention. If teachers work too hard, they risk burning out and dropping out of the education profession.

“There’s a perception out there that teachers only work eight-hour days for 10 months out of the year,” Urbanowski said. “The teachers I know would be happy to work ten-hour days, and many of them work longer than that.”

*

While state officials debate how to address the substitute shortage, education professionals think the solutions are obvious: pay substitutes more, streamline the application and onboarding process, and incentivize teaching.

Eric-John Szczepaniak, Grand Valley State University Student Senate President and former Kent ISD substitute teacher, serves on the Kenowa Hills School Board, where he sees firsthand how schools struggle with Michigan’s education funding system. The Michigan Legislature passed a $15.23 billion in pre K-12 spending, a 2.7 percent increase from FY 2019 to FY 2020, but many education professionals feel that the per-pupil spending formula does not adequately or equitably provide for high-need school districts.

“The Michigan Department of Education wants to make Michigan’s education rank in the top-ten in 10 years, but right now the Michigan Legislature is hardly spending enough to keep up with inflation,” Szczepaniak said. “We need greater investment.”

Most increased school funding pays off immediate expenses and retirement benefits, leaving little money left over for wage increases. Kent ISD school districts recently increased substitute pay from $75 to $90 a day, and they maintain an agreement to keep pay consistent between one another rather than competing with financial incentives.

The slight pay bump does little to attract candidates when job seekers can earn more money flipping burgers than substitute teaching. Leszlie Soda, West Michigan Regional Director at EDUStaff, considers McDonald’s and Taco Bell, fast-food restaurants that offer a $15 minimum wage and tuition assistance, to be two of EDUStaff’s biggest competitors.

“Fifteen years ago, there were more substitute teachers than there were assignments,” Soda said. “Today, substitute teaching is simply “not revered.”

Beyond receiving low pay, substitutes must complete a cumbersome application process, paying $50 for a required fingerprint background check and $45 to submit paperwork to the Michigan Department of Education.

Once the paperwork goes through, substitutes undergo a brief two-hour training workshop before beginning their first assignment. Some substitutes receive a staff-led tour around a new school, while others get started without any introduction.

To create a more welcoming environment, EDUStaff holds training sessions with administrators, and give suggestions like leaving behind detailed lesson plans, offering perks like a free lunch or personalized gifts, and greeting new substitutes in the front office.

“Culture is huge in a sub’s decision [to teach], and culture is free,” Soda said.

But the most significant challenge is attracting a new generation of students to teaching. As school districts froze wages, cut benefits, and tied performance evaluations to test scores under Michigan law, enrollment in Michigan’s teacher education programs plummeted by over 70 percent from 2008 to 2019, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education.

“It was a perfect storm,” said Amy Schelling, Director of Teacher Education at GVSU.

The typical substitute candidate was once a recent college graduate, trying to gain teaching experience. Now, education majors fill open teaching positions immediately upon graduation, depleting the pool of potential substitutes.

Szczepaniak strives to remain optimistic about Michigan’s education system, but finds himself feeling frustrated by the slow pace of change.

“Would it be better if we made some changes?” Szczepaniak said. “Yes. Will it get better in the future? Probably not by much.”

*

Within her first month of substitute teaching, LaPlaca built relationships with a handful of her favorite teachers and started exclusively filling in for them. It did not take long for her to figure out which schools to avoid entirely.

Even the cushier positions brought unique difficulties.

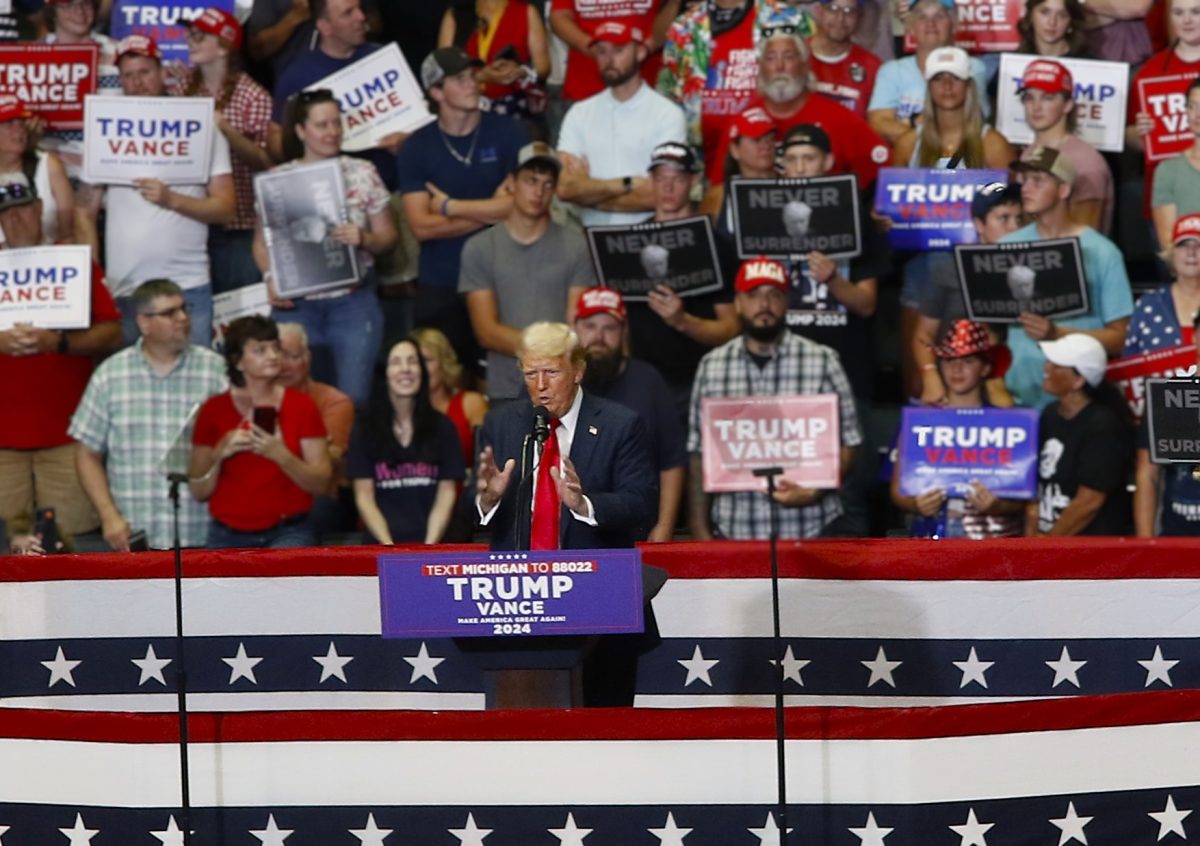

Once, LaPlaca found herself scrambling to prepare her class for an armed shooter drill that sprung up without warning. During the aftermath of the 2016 election, LaPlaca met with recently immigrated students, asking her if President Trump would deport them back to Mexico.

LaPlaca’s preparation for these situations was minimal, to say the least.

“There’s only one day of training, the lack of oversight is really incredible, and you could really be anyone,” LaPlaca said. “A babysitter would be more scrutinized than someone watching 25 children.”

When asked if she would consider subbing again someday, LaPlaca laughed.

“Subbing was a great education on the public education system; you see the highs, the lows, and everything in between,” LaPlaca said. “I give subs a lot of credit, but after seeing what they do… uh, no. It’s way too hard.’”