Second Brooks College Civil Discourse Symposium tackles dangers of global misinformation

Mar 29, 2021

On Thursday, March 25, the Grand Valley State University Brooks College of Interdisciplinary Studies Civil Discourse program held its second evening of a two-part virtual symposium that featured GVSU journalism professor Vandana Pednekar-Magal and acclaimed Chilean journalist Alejandra Matus. The discussion included topics like global journalism, global politics and the tension between people working to share accurate information and other individuals, organizations and governments trying to misinform the public having a major impact on the available information for civil discourse.

Co-sponsored by the Big Data Initiative, the School of Communications, the Writing Department, the Digital Studies Program and GrandPR, the aim of this year’s Symposium was to examine issues involving national and global journalism and misinformation. The event had over 95 participants, one of those being GVSU President Philomena Mantella and a number of other esteemed GVSU faculty.

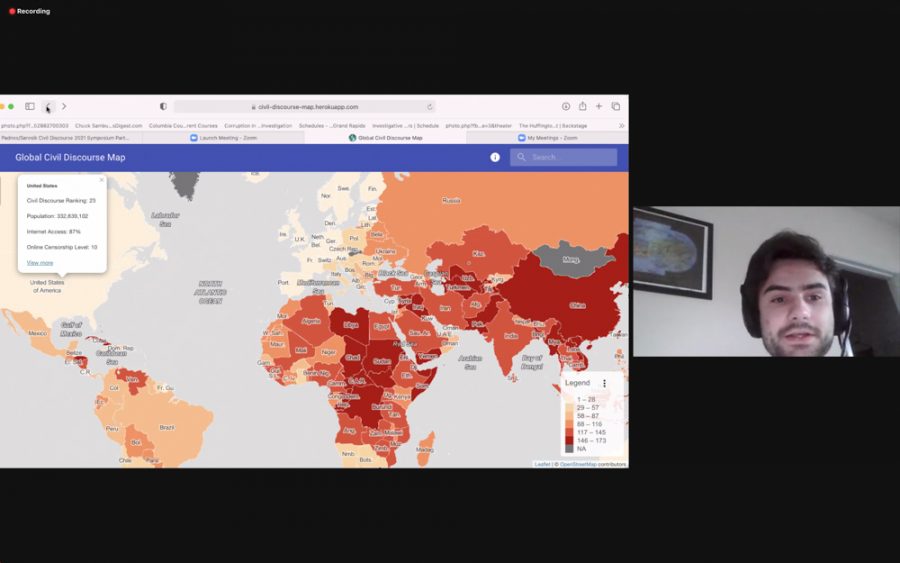

Brooks College Endowed Professor Jeff Kelly Lowenstein kicked off the night with the official launch of the Global Civil Discourse Map, a collaborative project between Kelly Lowenstein, a team of GVSU students from his IDS 350 course and the Computer Science Program.

The map itself, an interactive website that utilizes characterizing countries with specific information regarding their official ‘civil discourse rating’ like internet access, online censorship level, and other useful data-driven discourse information. The initial build of the map and accumulation of its data began throughout the fall semester in the IDS 350 class, whose members compiled and discussed the data, categories to highlight and new inputs.

This semester a new group of students has begun adjusting and improving the map and its contents. GVSU Computer Science and Information Systems student Aaron Bager explained that one of their new additions was making the map color-blind accessible by creating multiple color settings for the user depending on what type of color-blindness they have, as well as adding more information like creating a curated ‘latest news section and a live-updated populations number for each country

“Creating the color-blind accessibility addition was an important goal of the university project, and I know that Professor Kelly Lowenstein and my team believe that greater accessibility in a tool such as this is nothing but a benefit,” Bager said. “We are hoping to be able to expand our reach of the online map to people outside the United States, and we think it will make a huge difference in understanding and educating on the civil discourse research and work in the world today.”

Next up was a presentation featuring Chilean journalist and writer Alejandra Matus, who has written extensively on Chilean politics and the justice system and published a variety of books, the most controversial of which is The Black Book of Chilean Justice. Her work has also inspired a television series that has won several film accolades.

Matus’ discussion focused on the history of Chilean journalism and politics, and she highlighted how journalism and messaging in Chilean press was incredibly diverse but less objective historically, and they essentially aspired to defend an idea of society.

“Early on in Chile, there were leftist newspapers, right-wing newspapers, centrists, worker’s and women’s newspapers that covered a variety of issues,” Matus said. “I would say that these papers could be seen as an analog of the internet today, and we see similarities between the environments today. There was not a lot of pluralism in the papers, they all covered their own interests and issues, which most people seemed to be fine with during that time.”

Matus’ presentation highlighted how Chile’s dictatorship of military junta headed by General Augusto Pinochet, which began in 1973, controlled the media in the country and changed the press to cover only positive news about the government and would censor any papers publishing perceived slander against the government which caused chaos and violence at times toward citizens and media during the dictatorship until its end in 1990.

Matus also discussed the poverty levels and internet access issues that have impacted Chile’s media literacy and access to information. She explained how this has impacted Chile’s journalists in that there are not large numbers like there used to be when newspapers were the more popular form of media. She said that the internet and social media have completely transformed media in Chile and what is posted, seen and shared.

“The digital outlets are very poor in Chile, and there are not big teams of journalists working in digital media, it’s only probably one or two people focused on specific conversations or information when now there are enough resources to hire journalists to investigate anything,” Matus said. “Now we are seeing more anger towards journalists, like in the uprisings in Chile in 2019, who are trying to report on the injustice and the abuse of police. But in many ways, these are just citizen journalists trying to spread the word, they aren’t official journalists even though there are many out there covering the same thing. Understanding that more of this kind of journalism is being used is important.”

The second presentation featuring GVSU journalism and communications professor Vandana Pednekar-Magal highlighted media and press in India, and how misinformation has been used in that country both in and out of politics which has caused problems socially and culturally for citizens and the country’s leaders.

Pednekar-Magal has extensive work in the journalism field, including involvement in the production of two PBS WGVU documentary films, membership on GVSU’s Civil Discourse Advisory Board, and as a journalism professor at GVSU. Prior to moving to the United States, Pednekar-Magal was a reporter and feature writer in Mumbai, India, for the Economic Times.

During her discussion, Pednekar-Magal discussed how the press and internet have been used in recent times with the example of Narendra Damodardas Modi, who has Prime Minister of India since 2014, and his administration which has shut down and blocked the press in a number of instances in an attempt to stamp out oppression to their agenda. In 2018, the internet service was cut in India 134 times by local and national leadership, and there were 93 in 2019. When service is blocked in India, at times it has been for months depending on how broad the service shutdown mandate is.

“Blocking information by shutting down the internet is a handy tool for the Modi administration to have in their toolbox, and it’s really been historically used by autocratic regimes but we see Modi use his power to spread misinformation and fake news and propaganda,” Pednekar-Magal said. “Long internet blackouts like this have only been seen in countries like China and Myanmar, but never before like democracies in India. India is facing information wars of an unprecedented nature and scale, and citizens are bombarded with fake news on a constant basis from television news to global platforms. The difference is that many of India’s misinformation campaigns are developed and run by political parties in connection with cyber armies.”

Pednekar-Magal concluded by explaining that India’s misinformation danger comes more from the political side than from the press side, which is a stark contrast from the United States. She said that India’s the Modi administration’s grip on media and has shrunk the public sphere in the country and that this is the most potent danger because when the public sphere shrinks, it interferes with important public discourses and is a sign of the health of a democracy.

Following the two presentations, a short Q&A session ensued, with both presenters answering audience questions on their respective countries and misinformation in media and journalism. Many of the questions came from students and faculty members who were curious about the role of social media in global journalism, and how in global politics media and press can have a very contentious and at times volatile relationship.

Both presenters also highlighted the importance of young university and college-educated journalists and citizens paying attention to what’s being covered and what isn’t covered in the media, and encouraged audience members to try to diversify what they are engaging in with news. Both lastly commented on how the civil discourse map launched that evening could help to improve knowledge of civil discourse and its meaning and importance in media literacy, news, and global dialogues.

You can explore the Civil Discourse Map for yourself at this website. Feedback is encouraged.

To learn more about the event and see upcoming events in the Padnos Sarosik Civil Discourse Program and to learn more about the program’s work, visit their website. Follow their pages on social media for updates on new events and schedule dates.