Air pollution reached an all time high for the city of Grand Rapids over the summer of 2023. Reaching a peak point in late June, the city held the worst air quality in the United States. Visible smog and haze blanketed the entire state for multiple days, caused by chronic pollution issues and the rampant wildfires in Northern Michigan and Canada.

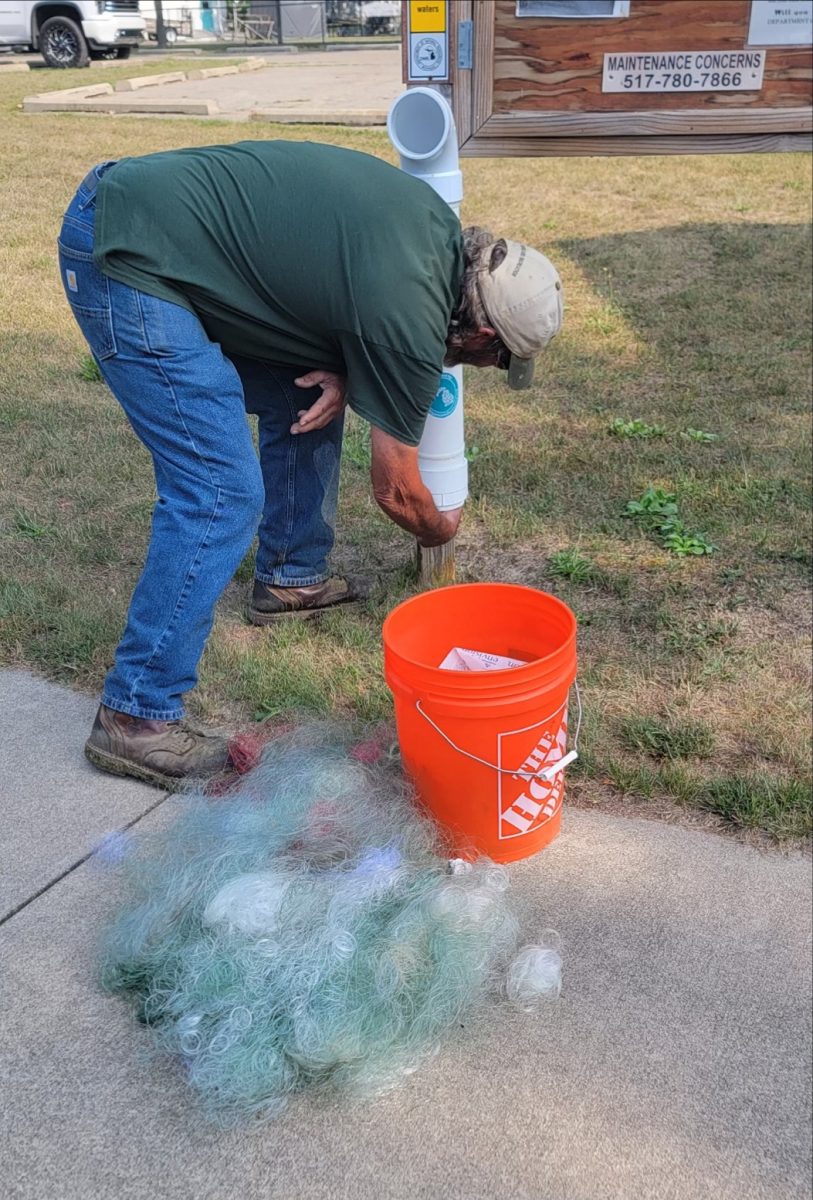

One particular wildfire, near Staley Lake, Michigan, began as an unconfined campfire that burned over 2,400 acres of land. The smoke from this and Canada’s wildfires made their way across the Great Lakes to settle in the air. The wildfires created a perfect storm of hot temperatures, low precipitation, dirt and dust that coalesced into a remarkably poor season for air quality. Many experts in the scientific community feel the uptick in negative natural phenomena has a direct correlation to the effects of years of climate change.

According to Elena Lioubimtseva, a Professor of Geography and Sustainable Planning at Grand Valley State University, extreme wildfires and record-breaking air pollution are just the beginning of what could be the future effects of climate change. Acute causes in air quality change can be attributed to the wildfires, though the greater sum of these forest fires can be followed back to man-made causes.

“There is no question about it,” Lioubimtseva said. “We have been experiencing more and more wildfires every year. It is very clearly linked to higher temperatures and changes in precipitation patterns, the same is happening along the Western Coast and the Mediterranean as well. Wildfires are very clearly correlated with climate change.”

An increase of rainfall throughout the summer generated perfect conditions for the devastating smog. The future of air quality in the United States and the world at large is a growing concern.

“It will get worse before it becomes better,” Lioubimtseva said. “With the higher temperatures and the higher levels of water vapor in the air, all the chemicals from the wildfires create a very unhealthy substance in the air.”

The community of Grand Rapids has been paying attention. Morgan Weststrate, a junior at GVSU, was surprised to see the city on the radar for pollution, especially when smog has been widely reported internationally.

“I remember as a kid seeing something in the newspaper about air pollution, but in a foreign country outside of the U.S.,” Weststrate said. “This is my first summer experiencing and hearing about it in the U.S.”

This kind of air pollution became more personal for many in the community when the haze covered Grand Rapids, though not every citizen was moved enough to stay indoors or change their summer plans.

“Personally the air pollution has not affected my plans in any way, but I have seen how it affects more people nowadays,” Weststrate said.

The severity of the smog, especially the visual effects, have prompted citizens and experts alike to call for change in human behavior as a civilization to prevent this from continuing in the future.

“I do think climate change contributed to the air pollution,” Weststrate said. “However I feel like this isn’t an easy answer. We can always be better and do better, but it’s a question of if we are willing to give up our lifestyles for the sake of our climate.”

Lioubimtseva said the fires themselves are mostly unpreventable if Earth’s temperatures continue to rise over the next few years.

“There is not that much we can do to prevent forest fires without addressing what causes them in the first place,” Lioubimtseva said. “We can try to adapt, we can try to mitigate the effects of forest fires with better forest management. I don’t think there is really a recipe for first management that can prevent wildfires with longer and longer dry seasons.”

Lioubimtseva believes protecting those who are able to mitigate the effects of forest fires and air pollution in their own communities is a good place to start as far as relieving the overall effects of these fires. Focusing on the human impact is also step for forest fire relief: placing special focus on communities who are most at risk, such as elderly people or those with respiratory diseases.

“We also need to think about the socioeconomic aspects of this vulnerability because people who don’t have access to air conditioning and those who work outdoors and can’t hide inside and those who are inevitably exposed really need to be protected,” Lioubimtseva said. “At this point, we need to focus more on the measures of social justice, making sure that those populations are protected.”