Community reading project discusses science ethics through book

Courtesy Photo / smithsonianmag.com The community reading project

Nov 8, 2010

Johns Hopkins harvested cells from the cervix of a black woman with cervical cancer. The cancerous cells, known as HeLa cells, have continued to multiply in laboratories for more than 60 years, thus granting “immortal life.”

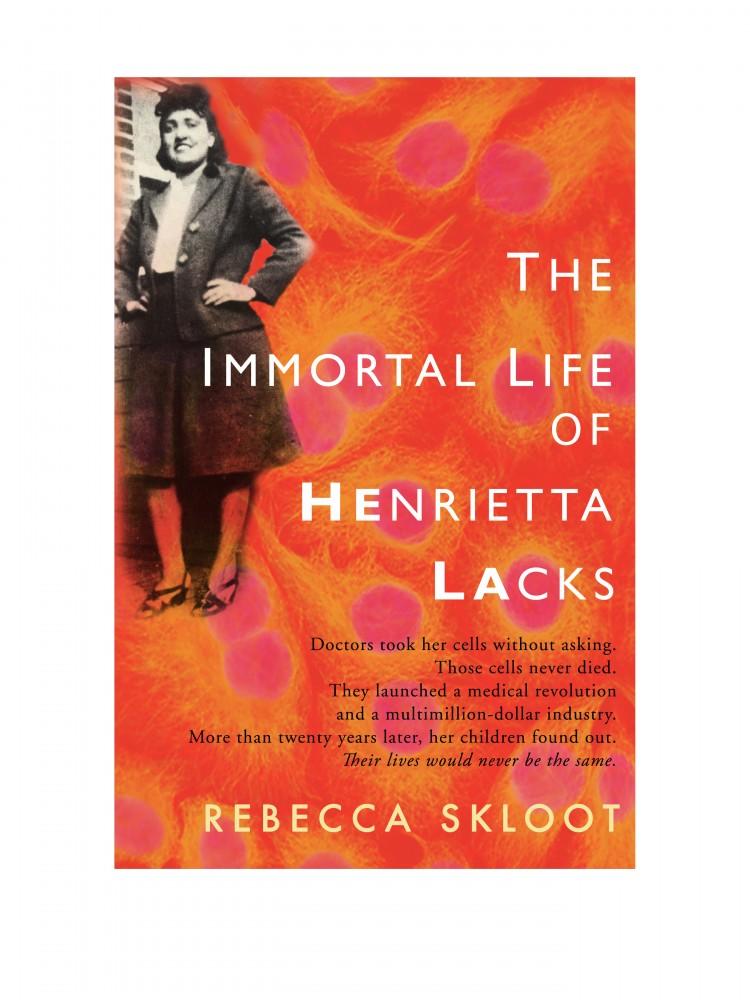

The Community Reading Project committee at Grand Valley State University has selected Rebecca Skloot’s “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” The work of nonfiction, published in February 2010 by Random House, discusses issues related to cancer research, genetics and medical ethics.

After its release, the book became an instant New York Times best-seller. Barnes and Noble selected the text as a Discover Great New Writers Pick for Spring 2010.

The book’s tagline reads, “Doctors took her cells without asking. Those cells never died. They launched a medical revolution and multimillion-dollar industry. More than 20 years later, her children found out. Their lives would never be the same.”

Scientists have used the cells taken from Henrietta Lacks to advance research in cancer, STDs and human longevity. Most notably, the HeLa cells were used to develop the polio vaccine.

However, ethical issues arise in the way doctors obtained HeLa cells. Because she used the free clinic in the “colored ward” at Johns Hopkins Hospital, some doctors of the 1950s believed they could use her cells for research without asking permission.

Furthermore, researchers went to the family years after Lacks’ death to obtain blood samples. While the scientific world debated the intricacies of informed consent, scientists allowed members of the Lacks family to assume they were being tested for cancer to get vials of blood.

The family did not know Henrietta Lacks’ cells were growing in laboratories until 20 years after her death when scientists began using the recent blood samples for research without patient consent.

Susan Mendoza, director of Integrated Learning, said the CRP committee selects books about complex issues applicable to many people.

“It is a compelling book, which pulls the reader into a story about a woman, her cells and how they change the world of medicine,” Mendoza said. “It also shows how complex that path is.”

She added everything in life is interconnected.

“In a world of video clips and Facebook posts, the book shows how life is much more complex than we expect, and the most benign of actions changes lives,” she said.

Sophomore Holly Zilke picked up a copy of “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” after she saw a favorable review of it in People magazine.

Zilke read the book on a trip to Lexington, Ky., and she especially enjoyed how Skloot describes the difficulties she encountered in writing the book. She spent more than 10 years conducting research.

Skloot interviewed Lacks’ family members to reconstruct her history. However, the writer needed to meet their approval before they answered her questions. Too many members of the media had disturbed the Lacks family over the HeLa cells, and too few members of the population understood the actual story.

“The author worked hard to learn enough to construct the story,” said senior librarian Debbie Morrow, a member of the CRP committee. “Because of racial elements, it’s a difficult story to tell. She had to gain the trust and empathy of the family.”

Morrow said the author invested her time and emotions in cultivating relationships with the Lacks family to learn and write the story of Henrietta Lacks.

Like much of the population, including those who for years mistook Lacks’ identity for Helen Lane, Zilke had heard of the cell line but did not know the true history behind HeLa until she read Skloot’s book.

“The polio vaccine was a huge thing, but people didn’t even know it was from her cells,” Zilke said.