GV alum reflects on career as assistant prosecuting attorney

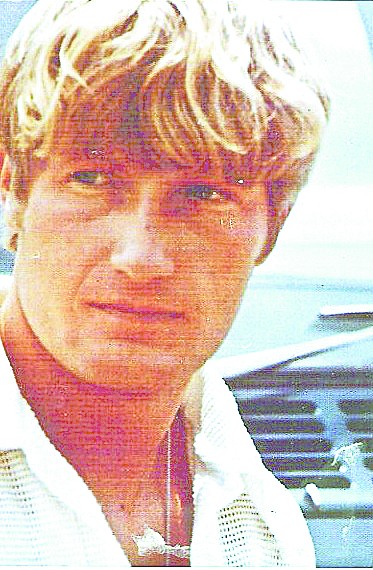

Courtesy Photo / Greg Babbitt Greg Babbitt at 22, on Grand Valley State University campus when it was still a cluster college

Nov 17, 2011

Greg Babbitt has seen some “weird cases” in the 31 years he has been an assistant prosecuting attorney in Ottawa County.

“I’ve had an individual who tried to hire somebody to murder their ex-husband, I’ve had drug cases and we’ve done criminal sexual conduct charges, and those can range from rape to child abuse,” Babbitt said. “I’m also involved in the medical marijuana cases in our county.”

But perhaps his most rewarding case happened three years ago during a double-homicide investigation, when two brothers robbed a jewelry store after murdering the owner and a customer who was there at the time. With no witness and no security cameras, Babbitt had to rely on the results of the crime scene investigation to give him something he could use. A single fingerprint left on a cigar box by one of the brothers was enough to convince the jury the defendants were guilty.

“Greg did an absolutely fantastic job of putting that together and putting the two responsible people on train and convicting them of first-degree premeditated murder,” said John Scheuerle, Babbitt’s colleague and fellow assistant prosecuting attorney for Ottawa County. “So that was really a significant accomplishment for him.”

A Muskegon, Mich., native, Babbitt was in the last group of men drafted during the Vietnam War, an unlikely first step on the path to what would be his career for the rest of his life.

“When I got drafted, it was interesting to me to find out what my rights were and so forth, so when I got out of the army I decided that would be the route that I was going to take,” Babbitt said.

After the war, he attended Grand Valley State University when it was still in its early stages as a cluster college and eventually went on to earn his law degree in 1980 from Cooley Law School.

Babbitt got his foot in Ottawa County’s law circuit shortly after, serving as a law clerk for two circuit judges in 1981. Later that year, he was offered the job of assistant prosecuting attorney, and has been there ever since.

“I found out I like being on this end of the law,” he said. “Someone needs to be the voice for the victims and that’s essentially what we do. Somebody has to speak up for the victims — those people have been injured or their families have been killed. I found out that I’m pretty good at it, and I enjoy it so I decided I would make my job on this end rather on the private end of the law.”

As assistant prosecuting attorney — not district attorney, a title Babbitt said is often confused due to television and film — Babbitt’s office represents members of the general public on cases ranging from mental health hearings to support matters with people on public assistance.

He said the toughest part about his job is the stigma about law enforcement that is a result of public perception.

“That perception that the prosecutors and police are somehow going to be violating your rights or their rights — it just doesn’t happen,” Babbitt said. “It’s great stuff for TV or books, but it just doesn’t happen that way in the real world.”

Despite the sometimes-negative place prosecuting attorneys have in the public eye, Babbitt said he is happy with the path he has chosen, and feels confident about the decisions he has made.

“We are the voice for the victims,” he said. “It’s so interesting that everybody is worried about the defendant — which is okay — but nobody worries about the victims and what happens to them. They didn’t ask to be the victim, and somebody has to be our there representing and supporting them. So, that’s what we do. “

And for Babbitt, that’s all it boils down to — being an advocate and representative for those people who have been wronged.

“When we’re done with a case, sometimes the victims will come up and shake your hand or give you a hug or whatever, because they’re more than appreciative for what you did, and the police did, and the courts did,” he said. “Because if we don’t do it, nobody will do it for them.”