CLAS faculty host first Research Colloquium of 2020

Jan 20, 2020

Grand Valley State University’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences makes it a habit to sponsor several research colloquia every semester. During each colloquium, faculty members from all over CLAS present the results of their recent research, new faculty or those returning from sabbatical being particularly encouraged to present. During the last meeting on Thursday, Jan. 16, four faculty members shared their recent projects with their peers.

Library Liaison Gayle Schaub and Graphic Design Professor Vinicius Lima presented on a several-years-long and still ongoing collaboration between the library and Visual and Media Arts.

“I used to work with Art and Design as their liaison, but this project came out of a study I did with colleagues in 2015,” said Schaub. “We did a large scale survey of students with library terminology. 60% of the student body of Grand Valley could identify only half of the fourteen terms we librarians use in the classroom.”

The seven least understood terms were journal, catalog, open access, subject heading, scholarly, source, and stacks. Schaub asked Lima if he thought his students would be interested in creating visual representations of the academic shorthand.

“It’s been an ongoing project since 2016,” Lima said. “The idea is to create these artifacts that teach students information literacy terms and concepts. We initially used design to promote understanding of the seven least understood terms, and later we approached other terms brought up by librarians, or terms specific to Grand Valley.”

Having already created visualizations for the terms that first inspired the project, students moved on to new topics.

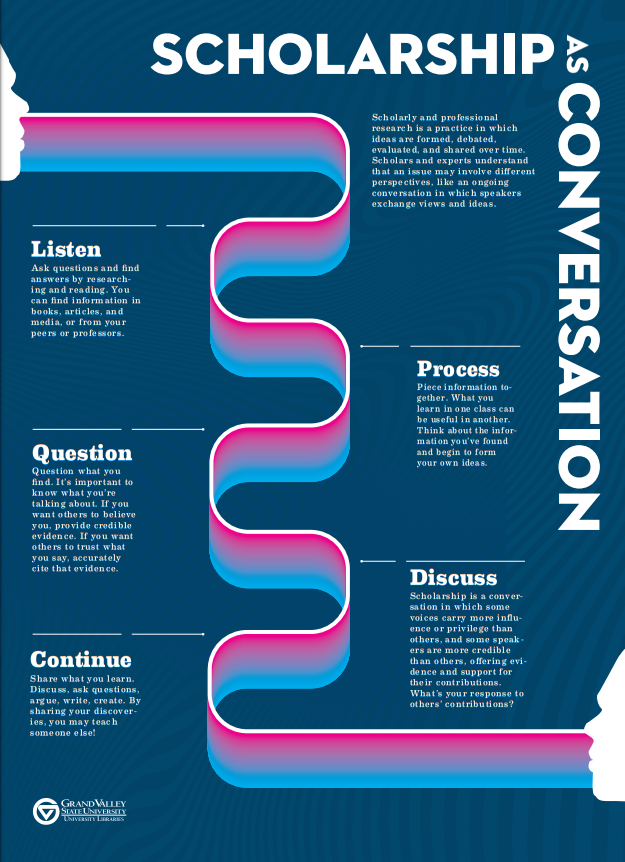

“The Association of College Research Libraries has a framework for information literacy based on six concepts,” Schaub said. “We’ve covered two since 2018 — ‘scholarship as conversation’ and ‘information creation as a process.’”

To create their visualizations, students utilized the power of color and shorthand symbols, in addition to taking inspiration from the library environment.

“The students really benefit from this experience,” Lima said. “They engage with concepts in two different disciplines. They take ownership of the work, they have to collaborate and develop confidence.”

Lima and Schaub weren’t the only presenters bringing students into their projects. Geology Professor Peter Wampler has been taking students with him to work on water filtration in Haiti for twelve years.

“I’ve been going since 2007, and I took my first student in 2008,” said Wampler. “I’m testing with students a method using sand and biochar, which are widely available in Haiti. That’s my goal at the moment, to find a solution using indigenous materials that the people there can make themselves. They’ve never had a way to make their own filters that work.”

Clean water is hard to come by in Haiti, with many living in rural areas having to walk miles to collect water from natural springs.

“Oftentimes it’s the kids, twelve years or younger — sometimes as young as six — who are doing this,” Wampler said. “They have to get water from two to three miles away, and even that isn’t safe to drink. We found that only 50% of people who have a water filtration device are using it. Many in cities buy water bottles. Water sachets costing about two to three cents are widely available, but they’re not regulated. When we did tests of them about half were unclean.”

The biggest danger found in Haiti’s unclean water was introduced to the country unwittingly after the devastating earthquake of 2010.

“A member of a United Nations group that came to help had asymptomatic cholera,” Wampler said. “It spread like wildfire and now a tenth of the country has it. It’s killed almost 10,000 people. It can be filtered out with a Sawyer filter, which is a very simple device. Water passes through the hose and comes out with essentially zero bacteria. We distributed 250 to families in the last two years, and we usually work in the hospital to do that. If every family had one of these, cholera would disappear.”

Wampler’s fellow presenter, Anthropology professor Deana Weibel, also traveled long miles for her own research. During a 2018 sabbatical focused on the intersection of religious belief and space exploration, she interviewed astronomers and astronauts everywhere from NASA laboratories in Texas to the Vatican Observatory in Italy.

“When I started doing this work, I had a lot of people tell me that it was ridiculous,” Weibel said. “That science crowded out religion when you’re doing scientific work. But my very first interviewee expressed that his whole trajectory as an astronaut was god-given. One of my more recent interviewees was a Quaker engineer who believes the ‘still, small voice’ humanity hears is telling us to go to space. It’s very easy to think of space and religion as separate spheres, but it’s even easier to push them back together.”

Though NASA’s favoring of the physical sciences prevents archeologists like Weibel from performing participant observation in space, she can still accomplish her work by observing and interviewing space explorers while they’re on the ground.

“I talked to people from about four different religions, and quite a few atheists on top of that,” said Weibel. “Doing work in space seems to change the way people think about these kinds of things. In a lot of cases, the motivation to do scientific work came from their perspective of religion.”

Interviewing at NASA in particular found a strong sense of Christian religious expression, tied in with American patriotism and exceptionalism.

“I talked to a technician on Apollo 11,” Weibel said. “He thought that our success, landing on the moon first, was divine assistance and proof of the special status of our country. The first religious expressions in space were Christian. When Apollo 8 orbited the moon, the three men on the ship read from the book of Genesis on Christmas Eve, 1968. It was very comforting for a lot of people, but was seen as a questionable division between church and state.”

Some of the non-Christians at NASA interviewed by Weibel were concerned by the monolithic atmosphere.

“One person I interviewed was talking to me about a sense of Christianity permeating NASA headquarters, and as someone who was not religious it was very frustrating for him,” Weibel said. “I’ve interviewed a Jewish astronaut who brought a mezuzah on board and NASA asked him to remove it because the small slip of paper inside was a flammable ‘safety issue.’ He noted that they had paper made from the same material strewn all over the place on the ship.”

Weibel’s findings, as well as those of her fellow presenters, were well received by their colleagues in the audience. Though those in attendance belonged to very different disciplines, the meeting proved to be an interesting exchange of perspectives between fields.