GV researchers tackle vaccine hesitancy

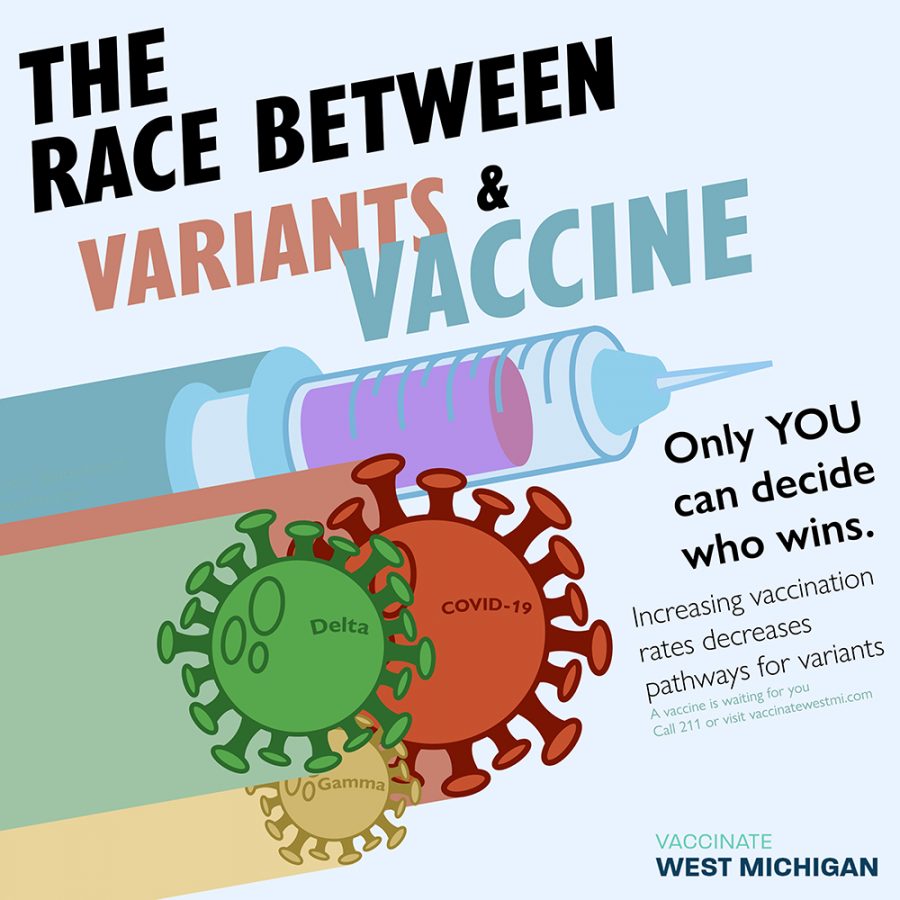

One of Fustero-Lopez’s designs, incorporating themes learned from their research into an easily-shareable inforgraphic. (Courtesy Vaccinate West Michigan)

Aug 30, 2021

Like many other schools, businesses and agencies, Grand Valley State University has set a vaccine mandate for its community, a decision made in anticipation of the full FDA approval for the Pfizer vaccine on Aug. 23. This clearance— which was industry standard, requiring the usual six months of data showing that a vaccine is both safe and effective— is widely projected to increase vaccination rates.

However, a survey from the Kaiser Family Foundation found that only 32% percent of unvaccinated adults said that full FDA approval would make them more likely to get vaccinated; obviously, a lack of confirmation from the federal government was not the main hurdle in overcoming the population’s vaccine hesitancy.

“There’s a wide range of concerns people have with vaccines,” said GVSU anthropology professor Kristin Hedges. “Many of them were pre-existent before Covid, like with the measles vaccine. Some people have no problems with vaccination itself, and just feel that we can’t trust something that was developed so quickly, or want to wait for a vaccine that covers the virus and all its variants.”

Hedges has been interviewing many unvaccinated adults with such beliefs as a part of her current research, an ethnographic study of West Michigan focusing on those who are vaccine-hesitant (or were vaccine-hesitant, and changed their minds).

“What we’re doing is conducting open-ended interviews, hearing people’s thoughts and perspectives on the vaccine, and then creating informational graphics that can easily be shared on social media,” Hedges said. “We’re cooperating with the Vaccinate West Michigan coalition— they’ve actually already started distributing the graphics we’ve been making. Typically with research studies you would wait until after data collection is finished to share the results, but we’re doing what’s called ‘rapid ethnographic data collection,’ due to the emergency conditions of the pandemic.”

The project is also partnered with the Kent County Health Department, who are providing quantitative data from a patient survey on vaccine perspectives to supplement the qualitative data of the interviews. Hedges is also working with two undergraduate research assistants; Maggie Wilson, an anthropology student, and Donovan Fustero-Lopez, a graphic design student.

“One of the goals was making these posts easy to digest for people who might not have the attention span or interest to read this information as a block of text,” said Fustero-Lopez. “By having bi-weekly meetings with my boss Kristin, we were able to discuss the exact wordings for each one based on a more complex set of information.”

Fustero-Lopez’s designs thus far, all of which can be seen on Vaccinate West Michigan’s website, tackle topics like why people who have had the virus should still get the vaccine and how lower vaccination rates create more virus variants. While many of these concerns are more specific to COVID-19 than the other, more regular vaccines of our day, Hedges points out that they represent a specific repeated pattern in history.

“Vaccination campaigns have always been big projects of public cooperation because they’re only as successful as people’s willingness to take them,” said Hedges. “We can trace back concerns all the way back to the smallpox vaccine— in fact, one of the very first anti-vaccination movements came from the UK over smallpox in the 19th century.”

Despite the foreboding air of history repeating itself, Hedges has also observed some positive changes in how people view vaccinations as a result of the current pandemic.

“What we’ve seen from some people is that the idea of vaccines and why they were necessary were harder to see when they weren’t right in front of your face,” she said. “For example, with measles, people had heard rumors about the Andrew Wakefield article— which I should note was retracted, and he lost his medical license— but they weren’t seeing that infectious disease day to day. They were viewing the choice as between getting the vaccine or not getting the vaccine, not between getting the vaccine or getting the infection. Now, with Covid disrupting our lives for going on two years now, it’s harder to ignore the potential consequence of not getting vaccinated.”

Despite the unignorable presence of COVID-19 in our society, misinformation about it and the vaccination process abound.

“There’s a lot of sources out there— we’re living in an infodemic at the same time as a pandemic,” Hedges said. “But Grand Valley students are great researchers. What I would encourage students to think about is what you really need to be weighing. I’ve heard people say, I’m not concerned, I’m in a low-risk category, what if there are side effects to the vaccine? But if you pivot the scale, we know there are long-term impacts from a Covid infection. Impacts on the heart, on the lungs, on the brain. It’s not everybody who gets it, but you can’t anticipate who will. That’s the risk you’re weighing.”