Consumerism vs. Religion: Christmas in the United States

Nov 29, 2021

Today, Christmas is arguably the most popular holiday in the United States: one 2017 Pew Research Center survey found that it was celebrated by 90% of Americans (though only 46% did so for primarily religious reasons). But Christmas wasn’t always the all-consuming national festivity it is now, and recent controversy over “irreligious” components of the celebration aren’t as novel as people might assume.

In the 17th century, Puritan colonists actually wanted to suppress the celebration of Christmas on grounds that it was already too secular. For one, there was no biblical evidence that Jesus was born on Dec. 25 of the Gregorian calendar: the Puritans were as well aware as modern scholars that the date of Dec. 25 was chosen by the 4th-century Catholic church because it coincided with Saturnalia, the Roman winter solstice celebration of “misrule.”

The Christmas traditions of the time weren’t exactly spiritual, either. They were characterized by excessive eating and drinking; casual and occasionally public fornication; cross-dressing (then called “mumming”); mocking established authority; and begging from door to door, often through caroling. The last of these was often combined with the threat of physical harm, occasionally escalating into outright home invasion. It’s perhaps not surprising that the Puritans preferred to ignore the holiday, even making it illegal in the colony of Massachusetts; from 1659 to 1681, celebrating Christmas was punishable by a fine of five shillings.

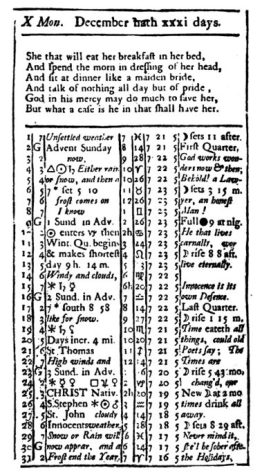

By the 18th century, however, New England’s war on Christmas had begun to wane. Benjamin Franklin, a born Massachusettsan, wryly described the holiday period as “O blessed Season! Iov’d by Saints and Sinners, For long Devotions, or for longer Dinners.” The descendants of the Puritans were warily interested in the “cheer” of Christmas. By the end of the century, even members of the clergy were willing to accept Christmas as a religious holiday: though they still acknowledged the unlikeliness of Jesus being born in December, they were willing to accept the draw of “entertaining” religious rituals, so long as they were “restrained by decorum.”

In addition, the former individualistic colonies were now a pluralistic republic. A holiday like Christmas, if widely accepted, could make for common ground between competing sects of Christianity. Though religious pluralism had been part of the United States since before its independence, increases in immigration had diversified the range of traditions wider than ever before. And in the way of the American melting pot, the Christmases of each were eventually assimilated into one singular holiday.

By the early 19th century, increasing numbers of churches opened their doors for Christmas-day services— and at the same time, shopkeepers were beginning to trade in Christmas presents. The spiritual and consumeristic aspects of the blossoming holiday weren’t considered contradictory at the time. Calvinism, the branch of Protestantism to which the Puritan ancestors of the new Americans had subscribed, had long-standing philosophical ties to business and the accumulation of wealth. German sociologist Max Weber even credited the “spirit of modern capitalism” to “Protestant work ethic.” The Calvinist idea that commercial relations should be regulated by charity blended well with the new idea of Christmas as a season of giving.

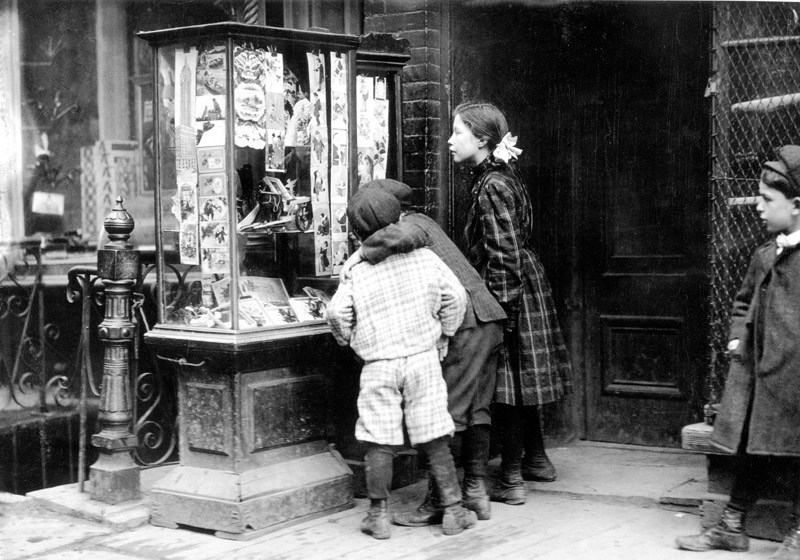

Many customs tied to commercialization emerged in the U.S. over the 19th century. The “Christmas trees” brought over by German Americans swept the nation, leading to new businesses in tree cutting and ornamentation. Less than seven years after the first commercially produced Christmas cards were made in England, American printers started making their own. Store owners began creating Christmas window displays for their shops, encouraging crowds of spectators to gather on sidewalks (which in turn led to pressure from merchants to keep the streets clear of those with a more Saturnalian approach to the holiday, for the protection of their customers).

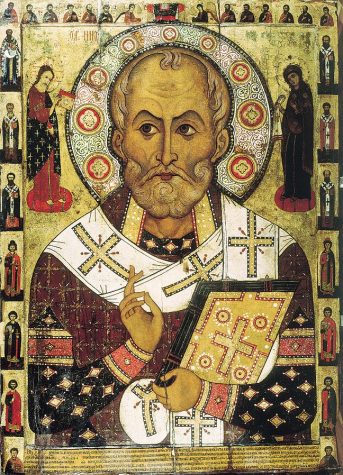

Perhaps the most emblematic evolution of Christmas in America was the creation of Santa Claus. The famous base of the legend, St. Nicholas, was a Turkish bishop who died on Dec. 6, 343. As Christianity spread from the Mediterranean to Eastern and Western Europe, the veneration of St. Nicholas spread with it.

Legends surrounding him were added, altered and conflated throughout the centuries. Two of the most popular stories include Nicholas gifting three sisters gold dowries so they could avoid prostitution, and resurrecting three brothers who had been butchered and brined by a cannibalistic innkeeper. Inspired by the story of the three sisters, 12th-century French nuns started giving gifts to poor children on Dec. 5, the eve of St. Nicholas Day. The practice became exceedingly popular throughout Europe— which led to a problem with the rise of Protestantism in the 16th century.

Protestants didn’t venerate saints, so what were they supposed to do with such a wildly popular celebration of one? None of the replacements for Nicholas satisfied, especially when many of them drew from pre-Christian pagan folklore.

Though the United States was a profoundly Protestant country, it was there that St. Nicholas was returned to his previous popularity, albeit in an altered form. In Washington Irving, better known from his short story “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” wrote a satirical history of New York that was published on St. Nicholas Day in 1809. His entirely fictional description of “Sinter Klaas” being central to spiritual life in the Dutch colony (including descriptions of his flying wagon and tendency to slide down chimneys to deliver gifts) intrigued and amused New Yorkers; and in 1823, right as Christmas began to be commercialized across the nation, “The Night Before Christmas” was published anonymously in the New York Sentinel.

Borrowing from Irving’s satire, the “St. Nick” described in the poem codified Santa Claus as he’s known today: white beard, round belly, bag full of toys. His bishop’s robe was replaced with a much more seasonal fur coat. The poem also separated him from his Catholic feast day— now he arrived on Christmas Eve, not the eve of St. Nicholas Day. Among the Dutch in New York, “Sinter Klaas” turned to “Sancte Claus” turned to “Santa Claus.” Just like the German trees and the British cards, the Dutch St. Nick swept the nation. For American families, the duality of his saintlike and materialistic qualities made him a perfect mascot for the developing holiday.

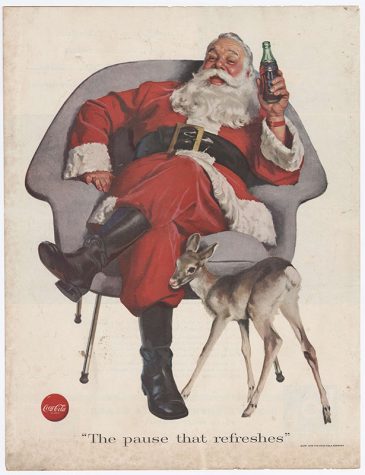

Not so much for many religious leaders, however, who were starting to be skeptical of the lavish spending surrounding the holiday. Santa was pulled into their criticism, as they feared he was obscuring the importance of Jesus. Denouncements of Santa Claus and commercialization continued into the 20th century. The first catchy demand to “Put Christ Back into Christmas!’ came in 1949, right in the middle of the Coca-Cola company’s decades-long “Coca-Cola Santa Claus” campaign. Christmas, already a major source of profit for retailers, became the centerpiece of U.S. commerce.

Today, Christmas is heralded by Black Friday sales the day after Thanksgiving. One major change in this seasonal consumerism was the elimination of usury laws in the late 20th century, allowing banks and credit card companies to apply predatory interest rates to loans. Issuing a credit card to poor or working-class populations with high credit risk was profitable, thanks to the ensuing fees and penalties for not paying off their debt. Companies urge consumers to buy their loved ones the perfect Christmas gift, even if they don’t have the money with which to do so. In 2020, the average American racked up $1,325 in holiday credit card debt; a number that’s up 8% from 2019, and 34% from 2015. This November, 13% of consumers (and 20% of parents with young children) are still paying off their holiday debt from last year.

Religious movements still criticize the commercial world’s approach to Christmas, though now those complaints are mainly centered around whether businesses appropriate Christian religious themes in their products and advertising— with appropriation being seen as a positive. The American Family Association keeps a list of “naughty or nice” companies, running on the metric that “if a company has items associated with Christmas, but didn’t use the word ‘Christmas,’ then the company is considered as censoring ‘Christmas.’”

One can only imagine how the Christmas relationship between religion and consumerism will evolve next.

Those interested in the history of Christmas, as well as the parallels between early and modern controversies over the holiday, can learn more by reading Bruce David Forbe’s “Christmas: A Candid History,” Stephen Nissenbaum’s “The Battle for Christmas,” and Penne Restad’s “Christmas in America.”