Religious studies panel discusses role of fasting in culture and religion

Mar 21, 2022

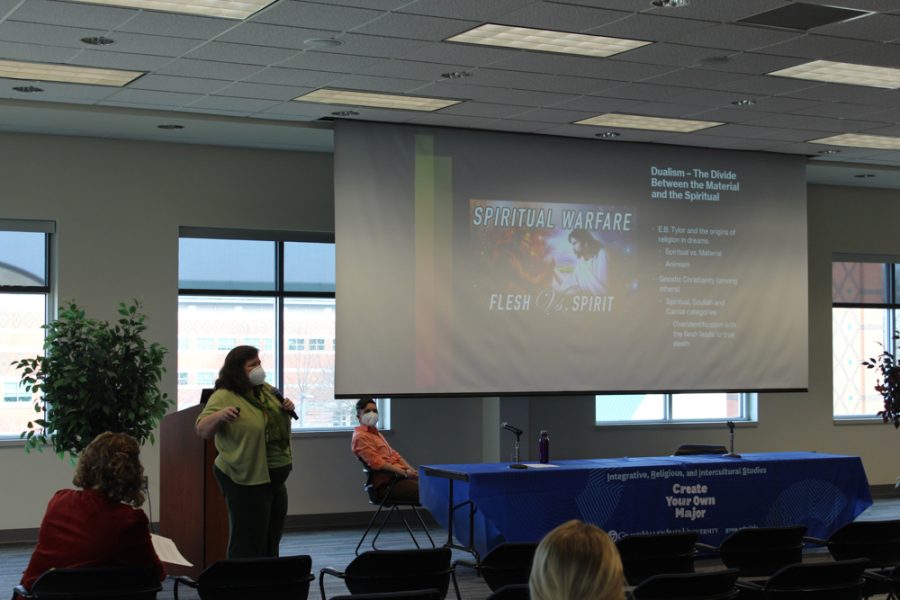

This time of year, the relationship between religion and food is often discussed during events like Lent and Ramadan. On March 13, the Grand Valley State University religious studies minor program hosted a panel discussion on the role that food plays in religion.

The first of the two panelists was professor Deana Weibel, who teaches in the Anthropology and Integrative, Religious and Intercultural Studies (IRIS) departments. She began the presentation by talking about fasting and religion.

Since many people aren’t familiar with fasting or eating habits due to religions during certain holidays, Weibel shared a bit of background information on why many religious individuals choose to participate in fasts or other dietary restrictions.

“In order to become a true spiritual person, you have to have control over your body,” Weibel said.

Weibel then went into detail about differentiating Kosher and Halal. Kosher foods are prepared in accordance with Jewish dietary laws, while Halal foods are prepared with Islamic law in mind.

“Kosher are laws laid down in the Bible that say what is fit to eat and what is not,” Weibel said. “Halal is very similar. It’s a way of understanding what’s fit to eat and not fit to eat in Islam.”

Many religions fast at different periods of time for reasons that depend on religious laws and culture. In terms of Abrahamic religions and their holidays, Weibel spoke about Judaism and Yom Kippur, Christianity and Lent and Islam and Ramadan.

“For many, fasting is giving up the flesh temporarily and returning with spiritual gains,” Weibel said.

While Lent takes place once a year for 40 days, Ramadan of Islam is a month-long period where participants fast every day from sunrise to sunset. Weibel used those examples to illustrate how fasting is the same concept but is utilized differently among all these popular religions.

When it comes to fasting in terms of the religions of India, many religions there take a different approach than many Abrahamic religions. Weibel brought up Buddhism as an example.

“You’re eating so you won’t be hungry but not eating anything else,” Weibel said. “The goal is to get rid of desire and desire for food.”

The discussion also included Jainism, in which fasting is extremely strict. Jains practice nonviolence towards all living things, including plants and animals. That makes for an interesting diet that mainly consists of certain vegetables.

“You cannot eat without causing harm because everything has a soul, you can’t even boil water,” Weibel said. “The interesting thing about Jainism is that if you are praying, you are protecting yourself from things like demonic attack, but you can’t pray all the time. This is why fasting is seen as something so beneficial spiritually.”

Weibel concluded her part of the presentation by highlighting parts of fasting that are common throughout the world. She discussed how fasting requires discipline and is often seen as a form of sacrifice, its association with mental and physical health benefits. She said that there are many variations of fasting, all with their own unique reasonings.

Dr. Dawn Rutecki, Assistant Professor in the IRIS department, spoke after Weibel and moved the discussion to indigenous dietary principles. She started off by acknowledging that everyone in Michigan lives on land that originally belonged to indigenous tribes, then moved to indigenous peoples’ relationships with food and how they see the world as a series of connections.

“Indigenous peoples understand connections with the world in terms of relationships,” Rutecki said. “These plants and animals are not only food, but they play active roles in these relationships.”

Rutecki heavily emphasized that indigenous people value their food before it’s even eaten, which makes each meal very important.

“In order for indigenous people to fully participate in their religious practices, they need to have control of food at the point before its food, while it is growing or in the land,” Rutecki said.

In certain tribes, animals and fish like salmon are blessed before being eaten.

“It’s clear from all of these examples that food is not only connected to these experiences and practices, but a foundation to these experiences and to sacred knowledge,” Rutecki said.